Buying Time in East Germany

- Share via

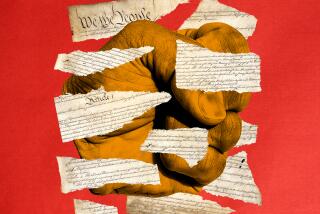

A few months ago East Germans paraded in the thousands, petitioning their government to adopt a less intrusive, less oppressive role in their lives. Now they are demonstrating in the hundreds of thousands, demanding a free press, free elections, an end to the “leading”--i.e., near-exclusive--role of the Communist Party in the political and social life of the country. It is worth remembering that for the last two generations the part of divided Germany now clamoring for sweeping reform has known only totalitarian rule and indoctrination, first under the Nazis, then the Communists. What those who have taken to the streets in ever greater numbers are saying is that even after 56 years of oppression, they remember the language of freedom and what it means.

Until a few months ago, the East German regime felt confident that it could resist the wave of change rolling over other Soviet bloc countries. The political embarrassment produced by the highly visible flight of tens of thousands of East Germans through Hungary and Czechoslovakia--with the cooperation of the Communist governments of those countries--clearly shook that confidence. Some presumed words of warning from Soviet leader Mikhail S. Gorbachev no doubt shook it even more.

Ultimately, the regime tried reform at the most primitive level. The Stalinst die-hard Erich Honecker was dumped, replaced by Egon Krenz, his protege but also someone who at least was prepared to murmur, however vaguely, about the need for change. The new tone, however, has done nothing to calm the agitation.

If Krenz has anything more specific in mind than buying time, he has yet to reveal it. He has shoved other septuagenarian members of the Politburo overboard, and allowed subordinates to talk about the desirability of revamping the entire government. As an earnest of his intention to permit freer foreign travel, he has reopened the border with Czechoslovakia, but rather than reassuring restive East Germans, that gesture has only prompted tens of thousands more to decamp to the West. Krenz is now reduced to pleading with East Germans not to run away. Suddenly some officials in West Germany, made nervous at the prospect of absorbing perhaps hundreds of thousands of additional refugees, are starting to echo that plea.

Will people listen? Perhaps, if evidence of genuine change were quickly to appear. But the kind of fundamental changes now being demanded--political pluralism, human rights, an end to the Communist Party’s exclusive hold on power--is change that by its very nature, as events in Poland and Hungary have shown, would spell the beginning of the end for the regime. So far, no one in power has suggested that this would be an acceptable course. In the end there may be no choice.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.