Brioche in Bed: A Crumbless Romance

- Share via

To some, Valentine’s Day may mean a candlelight meal in an elegant restaurant. To me, the ultimate Valentine’s meal is in bed. Not for giggly, prurient reasons, but because bed is the one place where you can have it all, including the sensual smell of freshly washed sheets, hung on the line to dry, and the newspaper.

My fantasy is a white wicker tray, covered with a lacy mat, laden with fresh orange juice, a piping-hot china pot of tea, raspberry jam in a special container (no label-wrapped jars, please) and mounds of brioches and muffins with butter. No croissants.

I do enjoy the luxury of croissants, particularly in France, where they are the usually delivered breakfast staple, even in the cheapest hotels. But let’s face it--it is impossible to eat a croissant without getting crumbs under one’s buns. The best croissants have wonderful large slivers that crumble. A non-crumbly croissant would not be worth buttering. And crumbs are the enemy in the land of good beds.

But brioches, the wonderful cake-like breads baked in fluted molds, have no flakes. Instead, they are delicate, light, rich, moist vehicles for butter and jam (jelly doesn’t do on brioches; honey might).

And, even though there is already a gracious quantity of butter inside the brioche from the making of it, the true brioche lover craves a brioche melting with even more. To guard against a buttery mess, snowy white napkins are the answer. Ironed damask napkins, that is--not the polyester ones that slip and slide on the bed, but lightly starched, nearly crisp ones that stay on one’s lap even on the most delicate of nighties.

Toasted brioches are good should Valentine’s Day lead to a second breakfast in bed. Thickly sliced, brushed with butter and run under the broiler, they have just the right amount of tension and texture between inside softness and outside crispness. Real competition for toasted pound cake, in fact, but pound cake is not for Valentine’s Day.

I learned to make brioches from Henri, the baker at Oustau de la Baumaniere, one of France’s famed three-star restaurant-hotels. My friend and I had arranged for lessons with him and paid a fortune (even in the days when the dollar was strong) to be able to drag ourselves out of our posh room and walk up the hill to the main hotel in the dark to work with him. Henri was immaculate in his chef’s whites and had apprentices and assistants scurrying around even before we arrived. We learned many other things, but brioches were our delight.

Into a giant mixer he dumped eggs (measured ever so accurately with a huge tin can), butter in copious amounts, yeast, flour and the barest hint of salt. He mixed it and kneaded it until it snapped when he slapped it on the counter, a clinging mass of shiny dough. He set it aside to rise while he pulled out the dough he had made the day before for us to shape and bake. It had doubled and been knocked down again and left to rise slowly to attract all the wild yeast cells in the air.

He pulled it out with his arms, strong from years of kneading dough, and pulled off a rock-sized hunk. He slapped it down on the counter, covered it with his hand and rolled it in the cup of his hand until it was smooth. There was an art in the rolling, but with practice it came. For each brioche he rolled out a little piece of dough to be inserted in an incision in the center, forming a little knob on top--like the finial of a bedpost.

They were doubled by the time the sun rose, and ready to be brushed with egg and baked. On we went to making tarts and other delicacies, with the aroma of the brioches underlying all our work. When they finally emerged, nearly all our work was completed. We took a break with the chefs, drank coffee from saucers and ate brioches, hot from the oven, brushed with butter, covered with jam, until we could eat no more.

We left the kitchen decidedly fatter and very weary but exhilarated with our lesson and with a hot brioche or two wrapped in large white napkins for a treat. We went back to our beds and slept the sleep of the just and dreamed of the brioches.

Obviously, this method of brioche-making is a true labor of love. But thanks to food writers Paula Wolfert and Abby Mandel, American women who have mastered French cookery and the food processor, great brioches may be made with less than five minutes’ work (in the food processor). After that the dough needs to rise only once (if possible), be refrigerated for a day or two and then shaped and baked. Brioches freeze beautifully, ready to be heated for a special breakfast in bed.

And, for those of us alone on St. Valentine’s Day, there is no sin in eating brioches in bed by yourself.

For these brioches, I use lightly salted butter. If you want to use unsalted, add one teaspoon salt.

BRIOCHES

1 package dry yeast

1/3 cup sugar

1/4 cup warm water (105 to 115 degrees)

2 1/3 cups bread flour

3/4 cup lightly salted butter, cool but not hard-chilled, cut into pieces

3 eggs

1 egg yolk, beaten, mixed with 2 tablespoons water

Grease and flour 10 small fluted 1/3-cup brioche tins or 1 (3-cup) brioche pan. (Brioches may also be baked in ordinary loaf pan.)

Dissolve yeast and dash of sugar in warm water. Combine bread flour and remaining sugar in food processor or mixer. Beat in cool butter. Add yeast mixture. Beat in eggs, 1 at time. Continue to beat until dough is shiny and glossy and forms long, slick strings that have adhesive quality. (If food processor turns off automatically, dough is ready.)

Place dough in oiled plastic bag or oiled bowl and turn to coat. Seal or cover and let rise in warm place until tripled. Punch down and let rise again, covered, 6 hours or overnight in refrigerator.

Take 2/3 of now spongy dough and, working quickly, form into 10 balls to fill brioche tins by 2/3. Make 2 crosswise cuts 1/2 inch deep in center of each ball. With remaining dough, form small pear-shaped knobs. Fit pointed ends of knobs into center holes, pressing firmly in place. Let loaves rise, uncovered, in warm place until dough has doubled.

Brush dough with egg yolk beaten with water. Bake on middle rack at 375 degrees until nicely browned, about 15 to 20 minutes. Cool slightly before removing from tins. Cool on rack. Keep in airtight container. Makes 10 brioches.

For Quick Brioche, cover kneaded dough in greased bowl with plastic wrap and chill in refrigerator 1 hour. Grease brioche tins. When dough is chilled, knead with floured hands until smooth. It should not require any more flour. Shape as described above. Brush all over with glaze. Let double 15 to 20 minutes. Bake at 375 degrees about 10 minutes, or until brown.

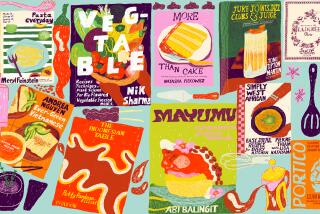

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.