Time to Take the Lid Off Prewar Iraq Policy : Indications of wrongdoing call for a special prosecutor

- Share via

The time has come to appoint an independent counsel to investigate the Bush Administration’s relations with Iraq over the 18 months leading up to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait.

An independent counsel--sometimes called a special prosecutor--is needed because, as Sen. Patrick J. Leahy (D-Vt.) summed it up in testimony this week before the House Judiciary Committee, there is evidence that high Administration officials may have committed criminal acts in connection with policy toward Iraq. Leahy is chairman of the Senate Agriculture Committee. A number of allegations about wrongdoing stem from billions of dollars in agricultural loans and loan guarantees that were made to Iraq, including loans made after strong internal doubts were expressed about Baghdad’s credit-worthiness. The loan guarantees made American taxpayers responsible if Iraq defaulted. Iraq did, to the tune of more than $1.5 billion.

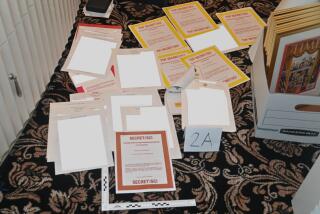

SIGNS OF STONEWALLING: There is further evidence that hundreds of millions of dollars in food loans were diverted by Iraq to buy weapons and other military technology, helping to make possible the buildup that preceded its invasion of Kuwait. Finally, evidence has been uncovered that some Administration officials sought to mislead Congress by altering documents to indicate that prohibited exports of military trucks to Baghdad were simply innocuous shipments of “vehicles.”

Congressional committee chairmen feel that they have probably gone as far as they can with their own investigations into what Washington’s policy toward Iraq involved, not least because they believe the Administration is being uncooperative. House Banking Committee Chairman Henry B. Gonzalez (D-Tex.), who has taken the lead in trying to expose the details of policy toward Iraq, complains that “the Department of Justice is progressing from foot-dragging to stonewalling.”

A similar view was expressed in highly unusual comments from the bench made by a federal judge this week. U.S. District Judge Marvin Shoob made his comments after he accepted a negotiated guilty plea by a former manager of the Atlanta branch of Italy’s Banca Nazionale del Lavoro who had been charged with conspiracy and fraud in connection with billions of dollars of loans to Iraq in the late 1980s. The loans included $900 million backed by U.S. agricultural credit guarantees. Referring to the plea by Christopher P. Drogoul, which effectively negated the defendant’s earlier promise that he would make a statement implicating others, Shoob said “this case needs a special prosecutor because . . . I’m getting a sanitized version” of what took place. Shoob left no doubt that his displeasure was with the Justice Department.

SCENT OF CRIMINALITY: A majority of members of the Judiciary Committee in the House or in the Senate can request the appointment of a special prosecutor if they believe that criminal wrongdoing involving federal officials has occurred. No specific criminal activities need be cited. The request goes to the attorney general, who must decide whether to pass it on to a three-judge panel that is empowered to name independent counsels. If the attorney general chooses not to do so, he must tell the committee why.

Atty. Gen. William P. Barr would be hard put, we think, to offer credible reasons for refusing to pass on a request for an independent counsel. Criminal wrongdoing almost certainly has occurred--in the misuse of the farm credit program for loans to Iraq, in the apparent alteration of key documents provided to Congress by the Commerce Department. The independent counsel law was passed in the wake of the Watergate scandal nearly 20 years ago, when it became obvious that in some cases there were reasons to doubt that the executive branch could be counted on to fairly investigate itself. This is, classically, one of those cases.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.