The Bioethicist: Answering the Very Toughest Questions

- Share via

In these tough economic times, are you looking for a career with a guaranteed future? A well-paying job in the fastest growing sector of the economy? The chance to be on the cutting edge of technological innovation without actually having to have technical expertise?

Then consider becoming a bioethicist. The hours are good; compensation can reach into six figures, and you never, ever have to worry about running out of big-budget ethical dilemmas.

Should that baboon liver be transplanted into the AIDS patient? How about pig livers for alcoholics? Should health insurance pay for the abortion that yields the fetal tissue that a daughter donates to help treat her father’s Parkinson’s disease? Precisely when does a parent have the right to ask a doctor not to resuscitate a dying child?

Increasingly, these are the sorts of questions that bioethicists are called upon to help answer. Advances in medical technology assure that these questions will only become more complex and more important.

“Just the Human Genome Project alone is the Full Employment Act for bioethicists,” says Arthur L. Caplan, director of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Biomedical Ethics, referring to the effort to map genetic diseases and traits.

Caplan estimates that there are about 2,000 bioethicists, mostly drawn from the academic ranks of theology and philosophy. “The field began in the embrace of the theologians,” he says, “as part of theological attempts to deal with such issues as abortion, brain death and euthanasia.”

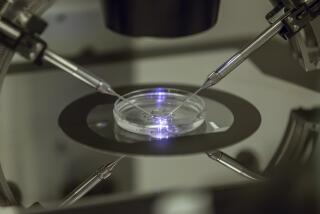

Twenty years ago, these ethical questions challenged society’s preconceptions of life and health. Today, ethical precedents in medicine can have enormous economic consequences. If a procedure is deemed “ethical,” such as in vitro fertilization, a new medical industry can be created. An ethical dismissal--baboon heart or liver transplants, perhaps--could stop a potential medical juggernaut in its tracks.

Over three-quarters of the nation’s 120 medical/academic centers have bioethicists and many hospitals now have their own “boards of ethics” to review procedures. But does the public want the medical establishment regulating its own ethics? Or will a market for ethical expertise begin to flourish as ethical concerns and economic constraints continue to clash?

Several states--including New Jersey, New York and Colorado--have funded “bioethics commissions.” Clearly, the health insurance companies need to have bioethicists on call, perhaps specializing in areas such as transplants, gene mapping and reproductive technologies. And the utilization review companies will want bioethicists for evaluating insurance issues. Pharmaceutical and medical device companies would probably be well-advised to have ethicists on staff to anticipate tough questions their innovations will surely generate.

Of course, labor unions may need bioethicists to assure that health plans are being fairly applied, and maybe groups such as the American Assn. of Retired Persons will want bioethicists to represent their interests to the medical community. Let’s not forget the judicial system, with its plethora of health-related litigation.

“The emergence of the bioethics expert in the courtroom has just begun,” says the University of Minnesota’s Caplan.

Adds Lawrence Gostin, executive director of the American Society of Law and Medicine: “I think ethics is becoming a commodity, and that’s becoming a problem. While we like to think about the ethical consequences of new technologies, we have never thought about the ethical consequences of having an ethics industry.”

For example, both Caplan and Gostin are concerned about whether there will ultimately be state or federal licensing of bioethicists. Should ethicists have legal training? Medical training? Theological training? Or philosophical training? While about 20 universities offer degrees in bioethics, the field can hardly be described as coherent.

Regardless, this is a field with a bright future. It’s a bit analogous to the recent explosion in intellectual property law. A decade ago, patents and copyright law was something of a legislative backwater. As courts enforced property rights and companies came to realize the value of intellectual property assets, activity in the area exploded.

Similarly, ethical questions have moved from the periphery to the very center of both economic and social concerns. What’s more, ethical advice is always going to be cheaper than medical treatments. For that reason alone, the job market prospects for tomorrow’s bioethicists look a lot healthier than the people they advise.