Death Creates New Uncertainties in Sino-U.S. Relations

- Share via

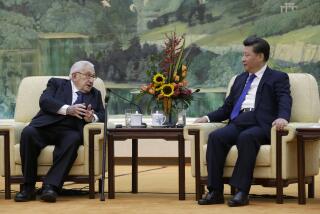

WASHINGTON — When Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping first began dealing with the United States in the mid-1970s as a replacement for the ailing Chou En-lai, he was so tough and so crusty that Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger once called him “that nasty little man.”

But over the next two decades, U.S. policy toward China came to be focused on Deng as China’s modernizer and as its ultimate decision-maker.

He was the Chinese leader who worked out the establishment of diplomatic relations with the United States and was viewed for years in Washington as the Chinese leader who could overcome or outlast critics of Washington in Beijing.

“In Sino-American relations, he was a hell of a lot,” said James R. Lilley, former U.S. ambassador to China. “This guy [Deng] was the guy that really pushed the relationship along, when it needed a push. He could break an impasse--on normalization, arms sales to Taiwan, whatever it was.”

Now, Deng’s death creates a series of new uncertainties, big and small, for the United States in trying to deal with the world’s most populous country.

Will China’s policy toward the United States change? Will there be a succession struggle or possibly an effort to “reverse the verdicts” of the Tiananmen Square crackdown of 1989? Will Chinese military leaders intervene to help settle divisions in the leadership, as they did behind the scenes after the death of Mao Tse-tung in 1976?

Deng had been out of political action for three years before his death.

U.S. officials have been saying for some time that the succession process has already taken place and that the Chinese Communist Party has already lined up new leadership under Deng’s last designated political heir, party General Secretary Jiang Zemin.

Yet Jiang, who is also president, is a much weaker leader than Deng, and that alone could possibly make it harder to work out China’s policy toward the United States.

Deng’s death “introduces a little risk that Jiang Zemin will come under pressure by various groups to make adjustments,” observed Douglas Paal, a China specialist in President George Bush’s administration.

No one rules out the possibility that someone else in the Chinese leadership might eventually challenge Jiang--just as Deng successfully wrested power from Mao’s chosen successor.

A few American specialists on China also believe that there could be internal divisions over the question of whether to revisit judgment of the massive pro-democracy demonstrations of 1989, which Deng himself officially branded a “counterrevolutionary rebellion.”

After similar but smaller protests erupted in 1976, the Communist Party eventually pushed through what was called a “reversal of verdicts,” withdrawing the official condemnation of the popular uprising.

“There’s no way that issue could be reopened while Deng was still alive, but I’d watch that in the next few months,” said Winston Lord, former U.S. assistant secretary of State for East Asia.

Current and former American policymakers agreed that there is little the United States could do to affect the outcome of any leadership divisions in China. “In China, it would only backfire if someone was labeled America’s candidate, just as if someone were Russia’s candidate or Japan’s candidate,” Lord said.

In the short run, administration officials said, China will want to keep up the appearance that everything is running smoothly.

Beijing will probably stick to plans for high-level meetings with the United States.

Vice President Al Gore is supposed to visit China this spring, and Jiang and President Clinton have tentatively planned meetings in Washington and Beijing within a year.

“Jiang will want to act as though this is a long-anticipated event that is not going to disrupt normal business,” one State Department official said.

But lurking in the background in U.S. officials’ calculations is their awareness of what happened after Mao’s death on Sept. 9, 1976--the only other time in the 48-year history of the People’s Republic of China that China’s top leader has died. Mao’s death produced what amounted to two succession struggles: one short and dramatic, the other longer.

Within a month, Chinese army and security officials arranged the arrest and imprisonment of Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, and three ultra-revolutionary allies, known as the Gang of Four.

That process temporarily ensured the leadership of Chairman Hua Guofeng, Mao’s handpicked successor. But it also gradually opened the way for Deng to begin to take control of the Chinese Communist Party.

Mao’s death also set off a struggle by the Soviet Union and the United States to curry favor with new Chinese leaders. Moscow sent a top official to Beijing to try to bring an end to the long-running conflict between China and the Soviet Union.

In Washington, President Gerald Ford responded to Mao’s death by sending a quick condolence note. “Dear Madame Mao,” it read. “Mrs. Ford joins me in extending to you our deepest sympathy.”

However, Mao’s wife was destined to spend most of the rest of her life in jail.

No one in Washington expects events in China to become as tumultuous as after Mao’s death. But no one is making firm predictions either.

China had some form of political upheaval after the deaths of other leaders too, including Premier Chou En-lai in 1976 and former Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang in 1989.

“There’s always this variable of Chinese traumatic convulsions,” Lilley said. “We’ve got to watch that very carefully.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.