From Fast Track to Bitter Feud

- Share via

The partnership should have worked.

There was racing legend Mickey Thompson, a land speed record-holder who built a second career promoting off-road car races.

And then there was onetime rock ‘n’ roll promoter Mike Goodwin, who had impressed Thompson in 1972 by corralling cross-country motorcycle racing in the Los Angeles Coliseum, giving rise to the sport of supercross.

The two men came together in the spring of 1984 in what was expected to be a dynamic mix of promotional genius. Instead, the partnership began crumbling within three months, leading to an acrimonious, four-year court battle that left Goodwin bankrupt, set the stage for his 30-month prison stay on a fraud conviction and, in the eyes of investigators, probably led to the 1988 murders of Thompson, 59, and his wife Trudy, 41.

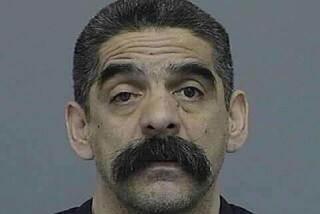

This week, 13 years after the San Gabriel Valley shootings, Goodwin was arrested but released from custody less than 24 hours later. During his day in jail, he was placed in a police lineup--in which two witnesses identified him--but then was released without being charged.

“When we feel we have enough evidence to present to the district attorney’s office for filing, a case will be filed,” Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Lt. Dan Rosenberg said afterward.

Goodwin has consistently maintained that he was not involved in the killings.

The highly publicized arrest Sunday night was the latest gambit in a long-running game of chess between Goodwin and investigators, who early on identified him as the primary suspect in what they believe was a murder-for-hire plot.

Sheriff’s investigators say that they are continuing to accumulate evidence in the case, and that they arrested Goodwin simply to compel him to take part in a police lineup he had fought to avoid.

“We are right on the edge of making this a very strong, solvable case,” contends Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Det. Mark Lillienfeld.

The passage of time, though, has made closing the case all the more difficult, he added. “People’s memories fade. Witnesses have died.”

The drawn-out investigation has been particularly vexing for Thompson’s only sister, Collene Campbell of San Juan Capistrano, for whom the 1980s were a decade of death.

First her son, a putative neophyte in the cutthroat world of drug dealers, was killed and shoved from a small airplane over the Pacific Ocean, a case that after three trials ended in the conviction of his two killers. The experience turned Campbell into a nationally recognized advocate for victims’ rights.

And then her brother, a man with whom she shared daily telephone calls, was shot dead just moments before she dialed his number only to have the phone go unanswered.

“I’m not sure our family can stand the justice system one more time,” Campbell said in the hours before Goodwin’s release. “But you can bet we’ll be there to see it through.”

Until they came together as business partners in the mid-1980s, Thompson and Goodwin traveled in overlapping orbits. Each was a headstrong entrepreneur, driven by passion and the desire to constantly challenge himself.

Thompson grew up in Alhambra, the son of a police detective, and took to motors and racing at an early age. Campbell recalls watching her older brother, then about 7, dismantle a washing machine to build a go-cart.

By his early 20s, Thompson was simultaneously developing a garage-and-parts business and embarking on his successful quest to set land speed records. Along the way in 1960, he became the first American to exceed 400 mph, achieving the feat at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah.

Thompson’s love of speed propelled him in other directions, too. He became adept at off-road racing, drove in endurance competitions and was also at home on drag strips, where he developed the “slingshot” design that put the driver at the rear of the chassis.

Goodwin, 56, grew up in Long Beach. The son of a Navy man, his own dreams of some day becoming an admiral dissipated in the sonic blasts of rock ‘n’ roll. He became a music promoter in the late 1960s, handling such clients as the Carpenters and eventually staging Janis Joplin’s final tour, “a traumatic experience,” Goodwin once said, that pushed him out of music.

A motorcycle enthusiast, he began promoting outdoor motocross shows before moving into stadiums and arenas in 1972, which gave him better control of the environment and afforded fans better vantage points from which to view the action. By the end of the decade, Goodwin’s supercrosses were taking in more money at the Coliseum than the annual UCLA-USC football game.

Thompson, already involved in promoting off-road car racing shows, began adapting Goodwin’s approach and set up his own series of arena events. But in the early ‘80s, his wife’s health problems led him to consider selling his entertainment business. Goodwin was the most obvious buyer.

“It was basically the same [business],” said Bill Marcel, who worked with Thompson. “He had all the infrastructure and the stadium contacts.”

Colin Cooper, a Tustin accountant and longtime friend of Goodwin, described the merger as a marriage of convenience between “two headstrong entrepreneurs who didn’t make good partners.”

“They came together because both of them, from a financial standpoint, needed the other person,” Cooper said.

The two struck a deal in the spring of 1984 in which Thompson agreed to retain 30% ownership and a small salary in the combined businesses. Goodwin was to take 70%, with a $300,000 salary and an escape clause allowing him to back out after 18 months. The men agreed to split expenses based on their percentage of ownership.

The venture ran into trouble almost immediately, with Midwest car events pulling in less money than anticipated and bills stacking up. Thompson later said that Goodwin asked him to deposit a total of more than $200,000 to cover bills, and he assumed that Goodwin was depositing even more, reflecting his 70% ownership.

Then Thompson discovered that Goodwin was not making deposits and that the bills weren’t being paid. Goodwin, who by then had stopped providing financial details of the business to Thompson, countered that the contract called for Thompson to cover losses at that point related to car events.

The clash of the off-road racing titans was on. In a series of lawsuits, the two moved from the arena into the courtroom, where Thompson was the victor, winning a 1986 judgment of more than $500,000.

The case helped push Goodwin into bankruptcy. It also indirectly led to the 1995 fraud conviction and a 30-month prison sentence. Goodwin and his wife were charged with applying for about $400,000 in bank loans without disclosing their failure to repay a 1986 loan. The couple were also accused of hiding more than $500,000 in assets by buying more than 700 gold coins, which vanished.

The bad blood between the two men spread beyond a simple falling out over business.

Weeks after the 1986 judgment had been entered, the pair were back in court fighting over ads that Goodwin took out implying that a Thompson event had been canceled. Goodwin claimed that friends in the Thompson camp told him that Thompson was spending most of his days plotting ways to ruin him.

In the months before the killings, according to court records, Thompson told friends that Goodwin had threatened to kill him. Goodwin has denied making such threats.

In one affidavit, a business associate said Thompson once told him over the phone, “Can you believe this? The guy threatened to kill me if he lost the civil suit.” Thompson, the associate said, went on to say that “the guy would not only kill him, but his whole family.”

In the days after the Thompsons’ bodies were discovered, investigators struggled to find a motive.

The killings took place at dawn as the couple emerged for work from their sprawling walled estate in Bradbury, an upscale San Gabriel Valley community with three miles of public roads and 10 miles of private gated streets.

Neighbors heard screams and gunfire, they told police, but saw nothing except the bodies on the ground. Thompson’s was in the driveway and his wife’s a short distance away, near a van that she apparently had been seated in when the gunfire erupted. Both had been shot several times in the upper torso. The killers left behind $4,000 in cash the couple was carrying, and $70,000 in jewelry that Trudy Thompson was wearing.

The murders clearly were the work of professionals, police said, and they began searching for two black men who witnesses in the neighborhood said they saw fleeing on bicycles, and a white man who was spotted on a bicycle in the area. Witnesses also said they thought they had seen the two suspected gunmen unloading bikes from a new maroon Volvo station wagon in the days before the killings.

As investigators tried to figure out who would have hired the gunmen, they began concentrating on Goodwin and his fractious relationship with Thompson as they ruled out other possible motives such as a romantic triangle, drug activity, robbery or loan-sharking.

“We have discounted all of those theories,” Det. Lillienfeld said this week. “They were obviously targeted for who they were. The timing of things showed a great deal of planning and sophistication.”

Soon after the killings, Goodwin rejected investigators’ requests for an interview, meeting with them once but declining to answer questions. Within weeks, he left the country, selling his Laguna Beach house and taking to the high seas in his 57-foot boat named Believe.

Goodwin reappeared in 1993 at U.S. District Court in Santa Ana for a hearing on a dispute related to his bankruptcy. There he was arrested on the fraud charges.

But charges in the murders never came.

Campbell, Thompson’s sister, posted a $250,000 reward for information leading to the conviction of the killers, and later upped it to $1 million. In late 1997, the case was featured on “America’s Most Wanted” after being spotlighted in two 1989 episodes of “Unsolved Mysteries.”

Since his release from prison on the fraud conviction, Goodwin has tried to restart his entrepreneurial career and worked as a marketing analyst for his friend Cooper.

Meanwhile, the Thompson case shifted from major news to Los Angeles lore, an unsolved double hit on an auto racing legend and his wife by mystery men on bicycles. At one point, the murders were relegated to the unsolved crimes unit of the Sheriff’s Department.

Lillienfeld and another detective were assigned to take a fresh look at the case a few years ago. They reviewed DNA evidence, pored through files, checked fingerprints and followed new tips. But they were not getting far in the investigation until the “America’s Most Wanted” episode was rebroadcast early this year.

At that time, investigators received a phone call that led to two witnesses who lived near the Thompsons. The couple reported that they had seen a man sitting in a car in the neighborhood sometime before the killings.

Investigators moved in March to put Goodwin in a lineup, but he refused and challenged a trial court order that he take part. A state appellate court ruled in June that Goodwin did not have to appear unless he was under arrest and in custody.

As a result, authorities say, Goodwin was arrested Sunday night at the modular Dana Point home he now shares with his father. Goodwin appeared in the lineup at the Los Angeles County Jail on Monday morning, where the new witnesses identified him as the man they saw 13 years ago.

The woman specifically pointed out Goodwin as the man she saw using binoculars and sitting in an old Chevy Malibu station wagon with Arizona license plates, Goodwin’s attorney said.

Investigators say they have also developed additional evidence in recent months and have turned to the Orange County district attorney’s office for help in investigating the case. In March, prosecutors began presenting evidence to an Orange County grand jury, and issued subpoenas for both Goodwin and his ex-wife. The grand jury ended in June without an indictment, but officials said the investigation is still underway.

Detectives have still not been able to interview their prime suspect in the case. Goodwin continues to refuse interviews with them, though he speaks to the press regularly.

“He’s claiming he has been framed,” said Lt. Rosenberg, one of the investigators. “We’re focusing on him. But we’ve never been able to eliminate him as a suspect because we’ve never been able to talk to him.”

Goodwin’s attorney, Jeffrey Benice, said Tuesday his client will not submit to an interview because he has a “constitutional right” not to do so and because he fears investigators will “twist and distort” whatever is said.

“Talking to authorities under their terms results in them twisting statements,” Benice said.

Investigators say they continue to uncover new evidence as they try to solve the classic whodunit. But they realize that time is not on their side.

“This case is killing me,” Lillienfeld said. “Thirteen years is just too vast a time period.”

*

Times staff writers Jerry Hicks and Steve Berry contributed to this story.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.