SLA Pursuer Loses MD License

- Share via

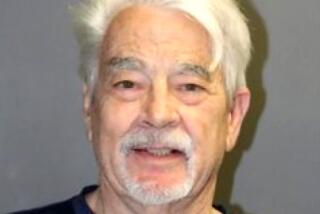

Jon Steven Opsahl won the biggest moral victory of his life in November when four Symbionese Liberation Army members confessed to the 1975 murder of his mother.

This week, the 42-year-old Colton doctor lost another important fight -- to keep practicing medicine in California.

Opsahl became the first doctor in the state to have his license revoked for prescribing medicine over the Internet without conducting a physical examination, a spokeswoman for the Medical Board of California said. The revocation is effective Feb. 21.

Papers released by the medical board Wednesday showed that Opsahl was accused of filling more than 11,000 prescriptions for “dangerous drugs, including controlled substances,” often with large and numerous refills. The prescriptions went to 1,500 patients in 2001 and 800 in 2002, the board alleged.

The drugs included Cipro, a powerful antibiotic used to combat anthrax, the painkiller Vicodin, codeine and various tranquilizers, said Dave Thornton, chief of enforcement for the medical board.

His conduct, the board’s decision said, “constitutes gross negligence, repeated negligent acts, incompetence and general unprofessional conduct.”

Medical board officials said Opsahl filled prescriptions through patient contacts made on Internet sites that have since been shut down, including ciproonline.com, officeinasnap .com, and prescriptiononline .com.

He charged $60 for a consultation, regardless of whether he filled a prescription.

According to medical board documents, a senior board investigator went undercover to obtain a prescription from Opsahl for Cipro, which was filled in November 2001. In addition, three patients complained about the physician, although just one testified as a witness in administrative proceedings against him.

The board noted that Opsahl was trained in preventive and addiction medicine, and had worked at a Permanente Medical Group (Kaiser) Chemical Dependency Recovery Program for five years, until 2000.

According to medical board documents, Opsahl’s attorney cited mitigating circumstances, contending that the doctor’s judgment had been impaired by the reopening of his mother’s murder case and by managed-care training that warped the physician’s sense of the doctor-patient relationship.

In 1975, Myrna Opsahl, a 42-year-old mother of four, was gunned down during a botched bank robbery in Sacramento in 1975 as she was trying to count church receipts. Opsahl was 15.

William Harris, Emily Harris Montague, Michael Bortin and Sara Jane Olson leaded guilty in November to that murder.

Opsahl had been instrumental in keeping the case alive, pushing investigators to pursue it and even launching a Web site to generate public interest. According to medical board documents, Opsahl’s “wound was reopened when some of the fugitives involved were arrested.”

But in a interview Wednesday, Opsahl disavowed that defense, saying that it arose from a conversation of “a few brief minutes” with a misguided expert witness.

“I totally objected to the whole idea. This psychiatrist threw out this nonsense about my HMO experience diminishing the value of the doctor-patient relationship for me, and on top of that he said I had this ordeal [involving the SLA murder]. He ruined my whole case.”

The medical board documents said Opsahl “cooperated with, even assisted” with the board’s investigation, adding that he was “candid, honest and forthright.”

Opsahl, whose license to practice has been suspended since May pending the case’s outcome, retained a measure of defiance at the medical board decision, and vowed to appeal.

“I did not do anything wrong in treating these patients,” said Opsahl, who went to medical school at Loma Linda University and has been licensed to practice in California for eight years.

He argued that the patients often had long-diagnosed problems with pain management that he ascertained from reviewing medical records they sent him.

“There was no physical exam that could have been done on these patients that would have altered the treatment,” Opsahl said.

Opsahl said he believed that the medical board went after him because it needed “an example” to steer doctors away from Internet care.

Board spokeswoman Candis Cohen said she hoped that the case would serve as a “cautionary tale” for doctors willing to fill prescriptions over the Web without conducting an examination and finding a true medical need.

Thornton said complaints involving Internet prescriptions began surfacing in 1998 and 1999 and have recently increased. They now involve more controlled substances, he said, such as painkillers.

But Thornton said the state has limited resources to crack down on such cases. In fact, Thornton said, he had to partially reassign the one investigator on Internet cases to more pressing concerns.

In addition, state officials said that prosecuting such illegal prescription cases can be problematic because witnesses often are reluctant to come forward.

*

Times librarian Penny Love contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.