In this column, parents who do math the old way

- Share via

NEW YORK — At the kitchen table in Brooklyn, N.Y., Victoria Morey has been known to sit down with her 9-year-old son and do something she’s not supposed to.

“I am a rebel,” this mother of two confesses.

What is this subversive act in which Morey engages -- with a child, no less?

Long division.

Yes, Morey teaches her son, who’ll enter fifth grade this fall, how to divide the old-fashioned way -- you know, with descending columns of numbers, subtracting all the way down. The formula works, and she finds it quick, reliable, even soothing. So does her son, she says.

But in his fourth-grade class, long division wasn’t on the agenda. As many parents across the country know, this and some other familiar formulas have been supplanted, in an increasing number of schools, by concept-based curricula aiming to teach the ideas behind mathematics rather than rote procedures.

They call it the Math Wars: the debate, at times acrimonious, over which way is best to teach kids math. In its most black-and-white form, it pits schools hoping to prepare kids for a new world against reluctant parents, who feel the traditional way is best and their kids are being shortchanged.

Many parents fall into a grayer area: They’re willing to accept that their kids are learning things differently. They just want to be able to help them with their homework. And often, they can’t.

“Sometimes I’ll meet up with another parent, and we’ll say, ‘What was that homework last night?’ ” says Birgitta Stone, whose daughter Gillian will enter third grade in Ridgefield, Conn., in August. “Sometimes I can’t even understand the instructions.”

Still, Stone agrees that kids should be thinking differently about math, and she doesn’t interfere by teaching her kid the old ways.

Morey, on the other hand, feels no guilt. She says her son was relieved to learn long division. “He wants a quick and easy way to get the right answer,” she says. “Luckily he had a fabulous teacher who said long division wasn’t in her plan but we were free to do what we wanted at home.”

And as for the concepts-before-procedure argument, she quips: “Would you want to go to a doctor who’s learned about the concepts but never done the surgery? Would you want your doctor to say, ‘I had the right idea when I removed your appendix, though I took out the wrong one?’ ”

Such reasoning is not unfamiliar to Pat Cooney. As the math coordinator for six public schools in Ridgefield, which over the last two years have implemented the Growing in Math curriculum, she’s seen a lot of angry parents.

One problem, Cooney says, is that they remember math as offering only one way to solve a problem. “We’re saying that there’s more than one way,” she says. “The outcome will be the same, but how we get there will be different.”

Thus, when a parent is asked to multiply 88 by 5, he or she will do it with pen and paper, multiplying 8 by 5 and carrying over the 4, etc. But a child today might reason that 5 is half of 10, and 88 times 10 is 880, so 88 times 5 is half of that, 440 -- poof, no pen, no paper.

“The traditional way is really a shortcut,” Cooney says. “We want kids to be so confident with numbers that it becomes intuitive.”

The Math Wars have been playing out since at least 1989, when the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics issued a document recommending concept-based teaching -- which was, the group says, distorted by critics and “exaggerated in every direction.”

“Our position is that math ought to be reasonable and kids ought to be able to make sense of it,” says Hank Kepner, president of the council and a teacher for the last 45 years.

The problem, he says, is that “a lot of adults view math as a cut-and-dried thing, not a method of reasoning.”

As for parents enforcing their own methods on kids, “You don’t want a kid pitted between parent and teacher,” Kepner says. “I would hope there would be an open conversation, involving the teacher.”

Sam Pennell, 10, of Brooklyn, hears about math a lot -- his dad, Mark, is an architect, and father and son have been known to discuss the volumes of cylinders to be filled with concrete.

Since Sam is good at math, his father supplements his classroom work with the old way of multiplying. “I’m doing this to broaden his perspective, to keep him from getting bored,” Pennell says. He thinks Sam could be challenged more at school, but otherwise he isn’t hugely bothered by the concept-based curriculum.

His wife, though, finds it mystifying. A writer with degrees from Barnard and Stanford, she still finds herself flummoxed by her son’s schoolwork.

“There never seems to be any explanation in the workbooks,” Allison Pennell says. “And there’s no textbook to refer to.” Her son doesn’t usually need her help, but when he does, she says, “I’m such a numskull. I don’t think I could pass fourth-grade math.”

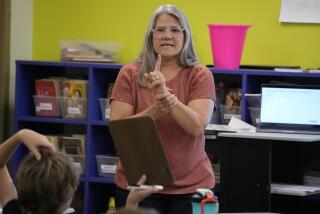

For teacher Melissa Hedges, a longtime elementary school teacher in Milwaukee, the key is to keep the lines of communication open. “I’ll ask parents to sit down and really have their child walk through what they’re doing and why they’re doing it,” says Hedges. “Even if it’s messy. The beauty in math comes from getting involved, knowing what you’re doing and why, exploring big ideas.”

Remember, Hedges says, “in the end, we’re all after the same thing. Sometimes it’s easy to lose that focus.”