Can scientists patent life? The question returns to the Supreme Court

- Share via

The thorny and unresolved question of whether life itself can be patented may come again before the U.S. Supreme Court, if it accepts a motion filed Friday by Santa Monica-based Consumer Watchdog. (H/T to David Jensen’s California Stem Cell Report.)

The issue isn’t a new one either for the consumer group or the court. Consumer Watchdog launched its challenge of a patent on human stem cells issued to the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, or WARF, in 2006. Since then the battle has been waged before the U.S. Patent Office, which overturned the patent then reinstated a narrower version; and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which hears patent appeals.

The group has challenged the patent on two grounds: first, that the work covered wasn’t novel or original, and second, that the Supreme Court has ruled that a “product of nature” can’t be patented.

That ruling came in 2013, in a case involving laboratory-isolated DNA. Even then, however, the court left the door open for patents of some biological products, notably “composite DNA,” which is synthetically created in the lab.

The court’s attempt to split hairs, so to speak, reflects its discomfort with the very question of where to draw the line on what sort of organisms can be patented.

As it happens, that question was placed before the court only indirectly by the Consumer Watchdog motion. The immediate issue is whether the organization had legal standing to appeal the patent office’s ruling in the first place. The appeals court threw out its appeal last year on the grounds that it hadn’t been injured by WARF’s patent, normally a prerequisite for bringing a lawsuit in federal court.

Consumer Watchdog’s lawyer, Daniel Ravicher at the Public Patent Foundation, says patent law explicitly allows parties that challenge a patent to appeal an adverse ruling to a higher court. He speculates that the appeals court raised the standing issue on its own last year because it was inclined to uphold the patent, and feared being overturned by the Supreme Court.

“This case is almost identical to the genes case,” Ravicher says. His goal is for the Supreme Court to accept its motion and order the appeals court to reconsider the stem cell patent on its merits. If that happens, the underlying issue of the patentability of life is almost certain to land back in the Supreme Court’s lap.

All this is happening, researchers say, because WARF made exceptionally broad claims for its patent rights and exercised them very aggressively. This is, in fact, WARF’s business; the nonprofit foundation was formed in the 1920s to exploit a patent issued to a University of Wisconsin professor on fortifying food with vitamin D, which it promptly licensed to Quaker Oats. By 1930, the deal was producing $1,000 a day. WARF also owns the rights to the drug Warfarin, which is named after the foundation.

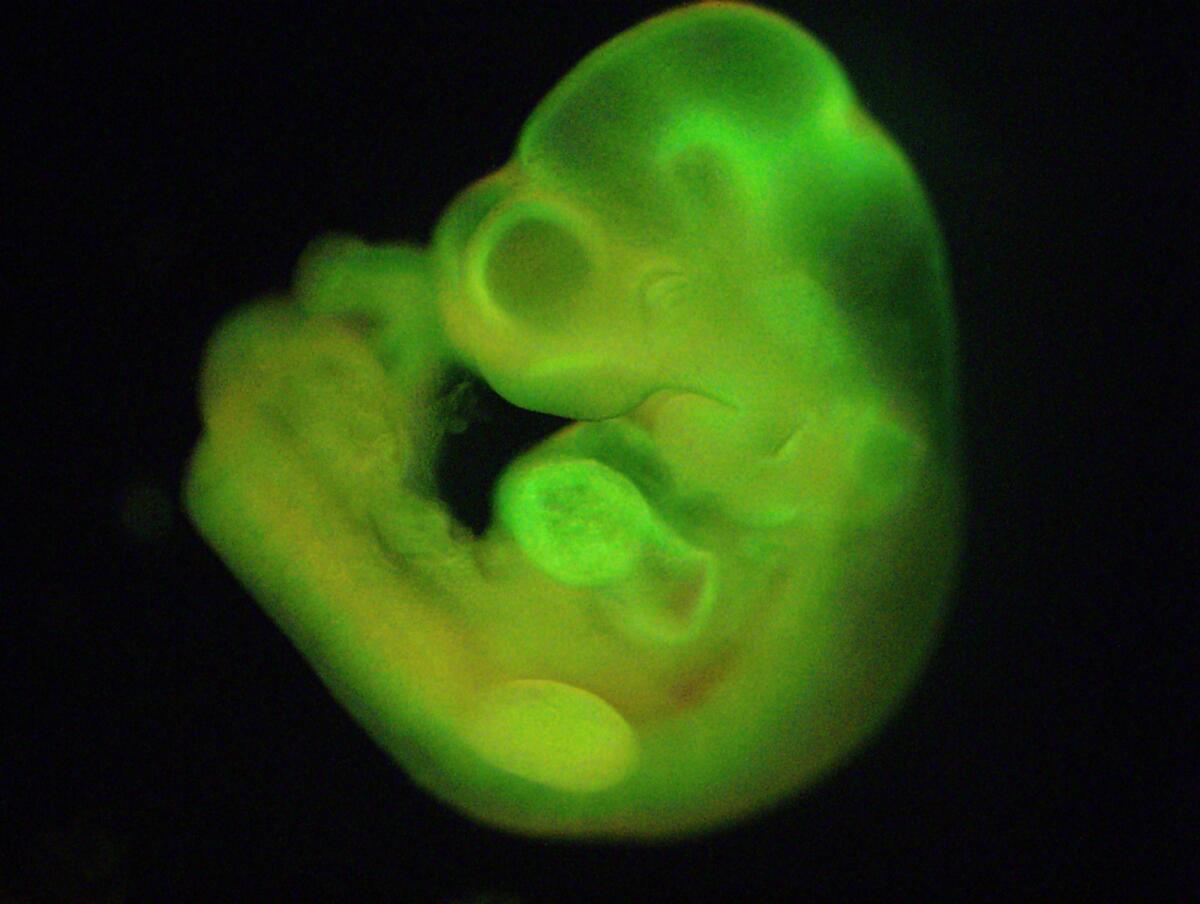

A stem cell patent was originally issued to Wisconsin’s James Thomson in 1995 (two more followed later), covering his extraction of stem cells from human embryos. WARF at first maintained that the patents covered the use of any human embryonic stem cells, and even products eventually produced by research using them.

The foundation demanded steep licensing fees of $5,000 a year from academic researchers and as much as $400,000 from commercial firms, plus royalties from product sales.

Eventually this backfired. When San Diego researcher Jeanne Loring was confronted by a demand for $75,000 a year from her start-up company--”that’s a lot, when your entire budget is $75,000,” she told me--she looked closely at the patents only to conclude that they should never have been issued.

The key to Thomson’s success, she contends, was that he was able to get his hands on human embryos at a time when other researchers could not; the techniques he used had been applied to embryos of other species and shown to be effective. “Had I or any other stem cell scientist been given human embryos and sufficient funding, we could have made the same accomplishment, because the science...was obvious at the time,” Loring says in a court declaration.

WARF disagrees. Thomson’s success, it says in its own legal filings, “was anything but routine....He identified the critical steps needed to generate and culture these cells....No prior art reference taught these insights.”

Loring, who now works at the nonprofit Scripps Research Institute, says she was determined to “remove any possibility that WARF could claim ownership of a commercially viable stem cell treatment.” Consumer Watchdog, meanwhile, became concerned that WARF’s demands might drain funds from the California stem cell program, which was just getting underway.

Indeed, it was reported in 2007 that WARF was demanding payments from the program, known as the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, or CIRM, and from its grantee institutions. (We’ve asked CIRM for elaboration, and will update when we hear back.) This was part of what Nature magazine termed an approach by WARF so aggressive it was “damaging its reputation, compromising its own university’s research collaborations and stymieing stem cell research.”

WARF soon backed off, announcing that companies wouldn’t need a license while they were sponsoring research at a university or nonprofit institution, though they still would need to pay once they brought the research into their own labs or brought a product to market. And it said specifically that CIRM and its grantees would be exempt from license fees.

Yet that wasn’t enough to head off the patent challenge. The value in that challenge goes well beyond whether WARF owns the right to human embryonic stem cells. It involves the question of how to strike a balance between providing researchers an incentive to pursue basic research, and stifling that research by excessive commercial claims. Then there’s the issue that the Supreme Court has toyed with, but still not settled completely: where to draw the line between a product of nature and a product of humankind.

Keep up to date with the Economy Hub. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see our Facebook page, or email [email protected].

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.