‘A sideshow to a sideshow’: Newsom sues to get party affiliation on recall ballot

- Share via

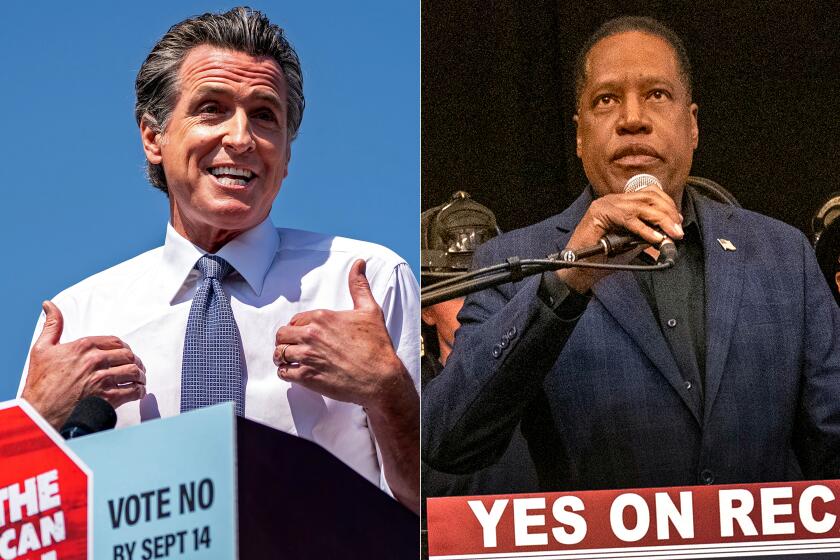

In a state where registered Democrats outnumber registered Republicans nearly 2 to 1, Gov. Gavin Newsom is now fighting to have his party affiliation listed on the recall ballot.

When Californians head to the voting booth for the still-unscheduled special election, the candidates seeking to replace the governor will be listed with their stated party preference, but a paperwork mistake made more than a year ago may preclude Newsom from being identified as a Democrat.

As first reported by Courthouse News, Newsom filed a lawsuit Monday against California Secretary of State Shirley Weber asking the court to require Weber to print Newsom’s party preference on the recall ballots.

“Would it be better for him if he is identified as a Democrat on the ballot? Absolutely, because this is California, where the information level among voters is extraordinarily low,” said Darry Sragow, a veteran Democratic strategist and publisher of the nonpartisan California Target Book election guide. “You can’t assume everyone knows who our governor is and that he’s a Democrat.”

Sragow still thought Newsom would defeat the recall even without his party affiliation on the ballot. But, he asked, why leave anything to chance?

The lawsuit states that after discovering their mistake, Newsom’s lawyers promptly filed a notice of his party affiliation with Weber on June 19. Weber declined to overlook the missed deadline and accept the notice. The former Assembly member was nominated to her post as California’s top election official by Newsom himself, and confirmed earlier this year.

Jessica Levinson, an election law professor at Loyola Law School, described Weber’s situation as “one of those exceedingly awkward moments” where the secretary of state is in charge of aspects of the election that could potentially help determine whether the person who nominated her to her position keeps — or loses — his job.

Amid what she described as “the continuing clown car of this recall,” Levinson characterized this particular development as “a sideshow to a sideshow.”

In the past, such as in the 2003 recall election targeting then-Gov. Gray Davis, party affiliation didn’t appear on the ballot next to the names of California elected officials targeted in recall elections. But a 2019 law signed by Newsom changed that, giving officeholders the right to have their party preference on a potential recall ballot. But the listing doesn’t happen automatically.

Conservative activists pressure election officials to drop people from voting rolls, claiming it invites massive ballot fraud in California

The updated section of California Elections Code stipulates that officeholders must ask to have their party preference put on the ballot during their initial seven-day window for responding after a recall notice is filed — which in this case would have been 16 months ago.

While Newsom responded to that initial filing on Feb. 28, 2020, he did not include his party preference “due to an inadvertent but good faith mistake made on the part of his elections attorney,” according to the lawsuit.

Weber’s chief spokesperson, Joe Kocurek, said in a statement that the secretary of state’s office had a “ministerial duty to accept timely filed documents,” and accepting any filing after a deadline would require a judicial resolution.

In the lawsuit, Newsom’s lawyers argue that applying the deadline would actually lead to “absurd results,” because “voters would be deprived of the very information that the Legislature deemed important for them to receive.”

The lawsuit also specifies that Newsom still filed his party preference choice “well before the recall election has been called, before the nomination period has opened for replacement candidates, and before the form and length of the ballot has been finalized.”

The relative importance of the Newsom team’s deadline error remains to be seen.

“If the recall is not successful, then we can say a huge headache, but in the end, no harm no foul,” Levinson said. “But if the recall, against all odds, is successful, then we can point to this as a huge unforced error and a turning point moment.”

California Republicans quickly seized on the gaffe in social media posts. Harmeet Dhillon, one of California’s two representatives on the Republican National Committee, shared news of the lawsuit with a crying laughing emoji on Twitter.

The official Twitter account of California’s Assembly Republicans said Newsom had “failed at basically everything since being governor; he can’t even fill out his campaign paperwork properly.”

The filing mistake is not Newsom’s first anti-recall stumble.

His team has also been criticized for not challenging a November 2020 court ruling that gave recall supporters extra time to collect the necessary petition signatures.

Then-Secretary of State Alex Padilla and Newsom theoretically both could haveappealed the ruling — although winning the appeal likely would have been an uphill battle, as the Sacramento County Superior Court judge presiding over the case had already granted extensions to the proponents behind two separate ballot initiative campaigns.

Garry South, a Democratic strategist who worked for Davis during the 2003 recall and for Newsom’s short-lived 2010 gubernatorial campaign, said that while he is sympathetic to the fact that recalls are fairly uncharted territory, he still believes the biggest blunder was not appealing the ruling that extended the signature-gathering window.

“It was a huge mistake for this decision not to be appealed,” South said. “It led us to where we are today — we’re going to have a recall and it’s going to be expensive.” A June analysis projected that the recall election — which at this point looks unlikely to remove the governor from office — will cost the state at least $215 million.

“When you know the outcome, it just feels like the last scene of this movie is just going to be the state of California lighting money on fire in the middle of the street,” Levinson said.

Times staff writer Phil Willon in Sacramento contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.