‘We got really lucky’: Why California escaped another destructive fire season in 2022

- Share via

Despite months of warnings fueled by extreme heat and drought-desiccated conditions, California’s deadly fire season ended with remarkably little area burned, with just 362,403 acres scorched in 2022, compared with more than 2.5 million acres the year prior.

Standing in a field of dry, brown grass in Napa this week, Gov. Gavin Newsom and several state officials gathered to mark what they described as “the end of peak wildfire season” in most of California, attributing the year’s relatively small acreage to massive investments in forest health and resilience projects and an expansion of the state’s firefighting fleet.

But although the worst of the season may be behind us, experts noted that the remarkably reduced fire activity is probably less a factor of strategy than good fortune.

“We got really lucky this year,” said Park Williams, an associate professor of geography at UCLA. “By the end of June, things were looking like the dice were loaded very strongly toward big fires because things were very dry, and there was a chance of big heat waves in the summer, and indeed we actually did have a really big heat wave this summer in September. But that coincided with some really well-timed and well-placed rainstorms.”

Indeed, two of the year’s biggest fires — the McKinney fire in Siskiyou County and the Fairview fire in Riverside County — were both left smoldering after the arrival of rainstorms, including the unusual appearance of a tropical storm in the case of the Fairview fire, which helped significantly boost its containment.

“Precipitation was coming right at the time when it was most needed,” Williams said. “Stuff was getting so dried out by these heat waves, and then at kind of like peak dryness, suddenly the skies opened up and soaked everything down, and it happened repeatedly.”

But although acreage this year was relatively small, 2022’s fire season was also far deadlier than last year’s, with nine fatalities, all civilians, compared with three firefighter deaths in 2021. Some of the deadliest fires, including the McKinney and Fairview fires, burned with significant speed fueled by dried vegetation, allowing little time for people to escape.

Fires this year were also destructive: By the end of its 10-day run in September, the Mill fire in Siskiyou County had leveled the entire neighborhood of Lincoln Heights in Weed. The McKinney and Oak fires in Mariposa County each destroyed nearly 200 structures, while the Coastal fire in Orange County in May claimed at least 20 homes.

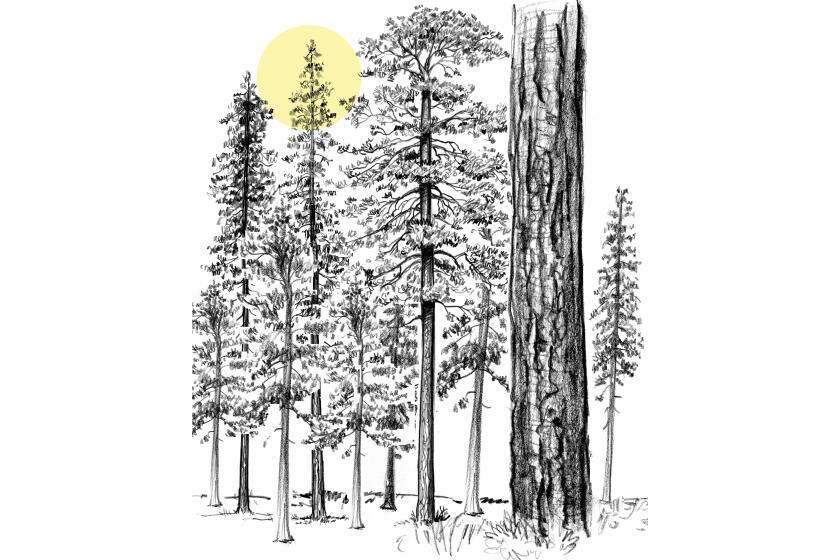

As California struggles with an increase in extreme wildfires, researchers are studying exactly what a healthy or fire-resistant forest looks like.

Still, some on-the-ground efforts appear to be working. The state has responded to 7,329 fires this year — about 200 more than this time last year — despite far fewer acres burning, indicating that crews were either extinguishing blazes more quickly or halting them before they grew too large.

The biggest blaze of the year, the 77,000-acre Mosquito fire in Placer and El Dorado counties, was much smaller than the biggest fire of 2021, the 963,000-acre Dixie fire.

Officials said several factors helped contribute to the overall tamer season, including a $2.8-billion investment in wildfire resilience projects over the last two years for forest management work, prescribed burns and community outreach.

“This past year, really, the tremendous amount of combined proactive efforts that were put forth by state and local and tribal and federal agencies here in California really did result in less damaging, less destructive fire impacts,” California Office of Emergency Services Director Mark Ghilarducci said during the news conference. “While some of this obviously is a result of weather, maybe a bit of luck, that sustained investment ... clearly made a difference this year.”

Joe Tyler, director of the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, said the agency completed more than 100,000 acres of fuels reduction each year since 2019, including about 20,000 acres in the last two months alone. That work was supplemented by local, federal, tribal and private partners, he said.

California also made significant investments in aerial support, including about a dozen new Firehawk helicopters that can carry more water than previous Cal Fire fleets and fly night missions, officials said. Six private fixed-wing aircrafts hired on short-term contracts also flew more than 2,700 hours on firefighting missions across the state this year.

“We are mindful that we are not out of the woods, so we’re not here with any signs of ‘mission accomplished’ in any way, shape or form,” Newsom said, “but we are here to highlight the work that has been done this year.”

The governor added that the state brought on an additional 1,350 firefighting personnel, which allowed for peak staffing as early as June.

Williams cautioned that officials “need to be really careful about taking credit for the luck that weather brings, because next year the dice are once again loaded for a really big fire season, and [they] have not treated all of the forests in California in one year.”

He added that other states under different management had similar luck this year, including Nevada and Arizona, which also avoided extreme fire seasons despite high heat and other conditions priming them for fire.

All four deaths in the McKinney fire highlight how older people are more vulnerable to wildfires and more likely to live where they are commonplace.

But Scott Stephens, a professor of fire science at UC Berkeley, said he gives Cal Fire and other state agencies credit for some of their programs.

“Some of the wildfires that started this year ran into some of their fuel treated areas, and they were able to make a stand in some of those areas more effectively,” he said. “That wasn’t the majority of fires by any means, but some ... actually reached these areas, and the proactive work I think is paying off in those regards.”

However, Stephens also noted that the state did not see any major dry lightning events this year, such as those that helped fuel hundreds of simultaneous fires in 2020 and 2021, and benefited from some rain. He said it’s important to stay vigilant, even in the face of improvements.

“There are really just two fire issues in the state that are paramount,” he said. “One is getting people that live in fire-prone areas better prepared for the inevitability of fire, and the second one is getting our ecosystem better prepared for fire, climate change, bark beetles and drought. … If we don’t get both those things done in really significant levels, we’re never going to get out of this problem.”

Officials this week remained optimistic about the outlook, and highlighted investments in new technology aimed at helping to detect and respond to fires sooner, including advanced aircraft known as FIRIS, or the Fire Integrated Real Time Intelligence System, and the establishment of a wildfire threat intelligence information sharing center co-managed by Cal Fire and Cal OES.

The state this year also established a Community Wildfire Preparedness and Mitigation Division to help communities better prepare for fires, Ghilarducci said. Investments in mitigation resources and home hardening included $100 million in community infrastructure grants and $25 million in outreach to high-vulnerability communities.

Newsom noted that the state next year will receive seven new C-130 firefighting aircraft from the federal government as part of a 20-year memorandum of understanding for shared stewardship of California’s forest and rangelands. About 57% of California’s forestland is federally owned.

Yet he also acknowledged that his four years as governor have been marked by climate volatility. Although 2022 and 2019 were relatively tame fire years, 2020 marked the state’s worst fire season on record, when more than 4 million acres burned.

“I don’t expect anything except extremes: extreme heat, extreme drought, extreme weather, extreme polar ends. The norm has been that sort of whipsaw back and forth,” he said. “I think we’re prone to overstate everything we did right in a year like this, but I don’t want to understate either the fact that this has been a flywheel.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.