What makes Tetris ‘the perfect game’? Experts break down an addictive classic

- Share via

The real story behind how Tetris became a video game phenomenon is more compelling than most imagined narratives.

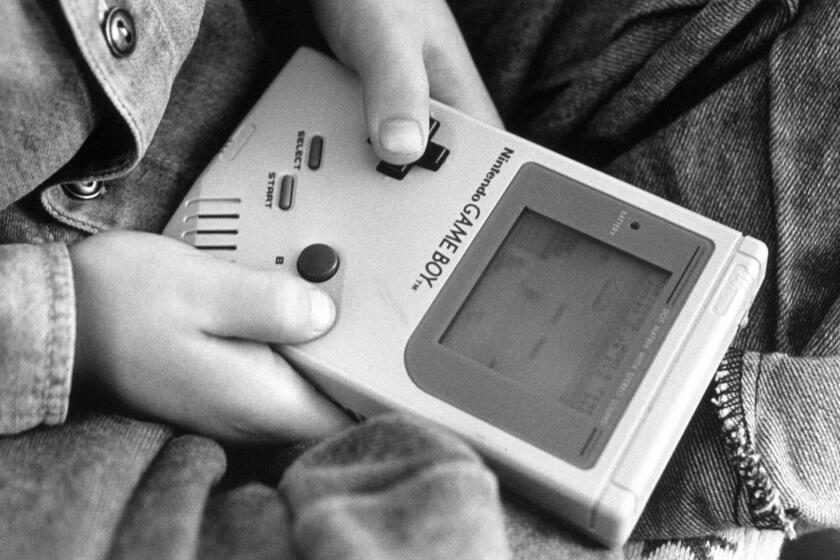

A computer game created by Russian programmer Alexey Pajitnov in the Soviet Union, Tetris eventually hit the burgeoning global market in 1989 as the launch title of Game Boy, a handheld console developed by Japanese company Nintendo, after Dutch American game designer and publisher Henk Rogers doggedly pursued the rights.

Much like the game itself, it’s a story that involved a lot of moving pieces that needed to be maneuvered just right in order for its players to achieve success.

This backstory is at the center of “Tetris,” out now on Apple TV+ after premiering earlier this month at SXSW. Directed by Jon S. Baird (“Stan & Ollie”) from a script by Noah Pink (“Genius”), the film follows Rogers (portrayed by Taron Egerton) after he is so dazzled by Tetris, which he stumbles upon at a game expo, that he bets everything on its success. Sorting out the complicated situation around the game’s rights propels Rogers to Moscow, where he meets and befriends Pajitnov (Nikita Efremov).

Taron Egerton stars in a strenuous, semi-diverting Cold War-era boardroom thriller about the battle to secure rights to the insanely addictive video game.

“We tried to make [the movie] as truthful as possible in the given circumstances,” said Pajitnov during a recent video call. “I was very fascinated with the movie because it was spiritually absolutely truthful. That’s exactly what happened to us, emotionally.”

But, “there was a lot of Hollywood in there because they squeezed like a year and a half of our lives into two hours,” added Rogers, who along with Pajitnov was an executive producer on the film.

Baird describes “Tetris” as a “Cold War thriller on steroids,” but at its heart is the friendship between Rogers and Pajitnov, which the pair boast “is still going strong after all these years.”

The movie “is really about two people, who on paper should be enemies, but at the end of the day find common ground because they’re both human and they both have families and they both love to play,” said Pink. “And we need to play more, I believe.”

While the story’s Cold War setting and political themes appealed to Baird, he was also drawn to “the sort of platonic love story between these two characters.”

Pajitnov and Rogers are “these polar opposites coming from different parts of the world,” said Baird. They’re “incredibly different, having very different cultural references and geopolitical references, [in a] story of East and West coming together … That was what really interested me about it, and it just so happened to be about this famous video game.”

This “famous video game,” of course, is one of the best-known and bestselling video games ever. And the film’s version of Rogers describes it as “the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen.”

“This game isn’t just addictive,” says Rogers in “Tetris.” “It stays with you. It’s poetry — art and math all working in magical synchronicity. It’s the perfect game.”

It’s a sentiment that Pink, who grew up playing Tetris with his siblings during road trips, stands by.

“For me, what makes it the perfect game is that it’s a puzzle,” said Pink, who attributes Tetris’ addictive qualities to its simplicity. “It’s like your favorite story that you love to hear over and over again, but every time you hear it, something new comes up. That’s Tetris for me. Because you know what blocks are coming, but every time it’s a little different, and every time you play, it ends up a little differently.”

Alexey Pajitnov created the original game 17 years ago. Time hasn’t changed our fascination with the cascading tiles.

But “perfection” is a loaded concept, especially if you ask games scholars.

“It encapsulates a lot to say it’s the perfect video game,” said Tracy Fullerton, a USC professor and the director of its Game Innovation Lab. “Perhaps you could say that it was a perfect video game, especially a perfect video game in combination with the Game Boy platform, which I think was the thing that really made Tetris as massive as it was.”

Jennifer deWinter, the dean of Lewis College of Science and Letters at Illinois Tech, was more direct.

“There’s no such thing as a perfect game,” said deWinter. “But if I had to ponder the brilliance of Tetris — and I think that that is a fun thing to ponder — Tetris provides a pattern-based abstraction that allows people to go into a flow state, readily.”

Meaning, Tetris draws players in to become so absorbed in the game to the point that outside distractions get tuned out. And that’s addictive.

According to Fullerton, Tetris “is one of the best games and continues to be one of the best games ever made” because “it’s so satisfying.”

And this satisfaction of sorting things out and fitting pieces together, deWinter explained, stems from the fact that “human beings love pattern matching” at any age.

“In terms of this elegant, pared-down, pattern-matching game, Tetris is it,” said deWinter. “It’s the godfather of all those types of game. And continues its own life to now, [and] it continues to have tremendous influence on other games, either as mini games or as in the casual game revolution and all the pattern-matching games that we start seeing there.”

Pajitnov, who developed the first version of Tetris in 1984, was inspired by the puzzle game pentominoes, which involved piecing together certain shapes created by five squares. This original Tetris was a computer game that eventually made its way to arcades and consoles.

As Fullerton and deWinter both note, it was the marriage of Tetris to Game Boy that catapulted both to success.

“I don’t think Tetris would have ever become as big as it did had it not been the Game Boy game,” said deWinter. “What the Game Boy does is it provides everyone a small, cheap, handheld computer game device … and Tetris becomes the cultural phenomenon that we know, because it’s packaged with this platform.”

“I played Tetris on Game Boy, and I remember being astonished,” said “Tetris” producer Matthew Vaughn. “The technology was mind-blowing back then.”

According to the Tetris Co., over 520 million units of Tetris have been sold worldwide, and the game has been downloaded more than 615 million times on mobile devices. There have been numerous scientific studies around Tetris, delving into everything from why the game is addictive to how playing the game affects those with anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder.

And Tetris and Game Boy’s pairing was mutually beneficial.

At first glance today, Nintendo’s Game Boy can come off as a hefty, dull gray block of a handheld console.

“I think Tetris, in many ways, was responsible for the success of the Game Boy,” said Fullerton. “Not just as a child’s toy, but as something that business people or older people might carry with them.”

It was not until the “Pokémon” series launched in 1996 that the Game Boy had its next blockbuster video game, so it’s safe to say a phenomenon with the longevity and widespread appeal of Tetris was significant to the handheld console’s success.

Baird admits he is no gamer, but he said that working on “Tetris” changed his perception of the game because it forced him to revisit it.

“It made me play it more so I wouldn’t be embarrassed when I actually eventually met Henk and Alexey in person, just in case they challenged me to a game,” said Baird. “I’ve got OCD [obsessive-compulsive disorder], and it really appeals to me, this game, because you compartmentalize everything, and then it disappears.”

In the end, as Baird discovered firsthand, whether Tetris is the “perfect” game may be less important than the ways it continues to help people connect, just as it did Pajitnov and Rogers in the late Cold War.

Playing Tetris because he was working on the film, said Baird, “has bonded me closer with a 13-year-old who previously probably wouldn’t want to spend that much time with her father playing computer games.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.