‘A Memoir Blue’ is a lovely video game exploration of a mother-daughter relationship

- Share via

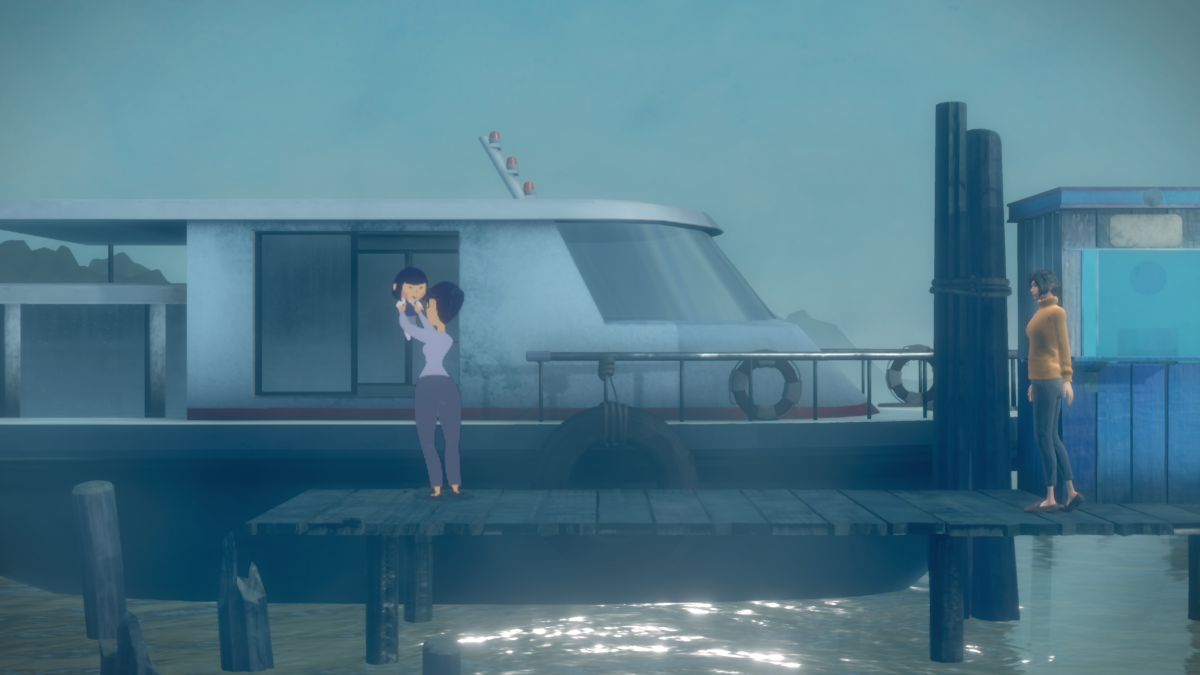

“A Memoir Blue” starts with a phone call. It’s a vibrating ring we won’t answer, at least not right away, though we can move the cursor to mimic a swipe. In this game, the communication is internal, a dialogue between the player and a character lost in thought. Soon, the young woman we’ve just met will be drowning in a family room full of water, a house that’s been turned into a fishbowl. Grab a boombox, smash the floor, and shortly we’re on a train.

Reality is abstracted in the settings of “A Memoir Blue.” The emotions, however, are grounded.

“A Memoir Blue,” over the course of its 90 minutes, wants to lull us into a dreamlike state, to telegraph to us scenes integral to a woman’s life and make them feel a bit magical. Specifically, the game will zero in on a relationship between a mother and a daughter. We’ll move it along, as throughout we’re coaxed to interact with the images in a newspaper, the lights of a city or an object as simple as a stamp. This is an interactive short film where play exists to calm us. We don’t solve puzzles, but we bring memories to life. We aren’t challenged, and in turn we are free to contemplate, to see an image from a shift in perspectives.

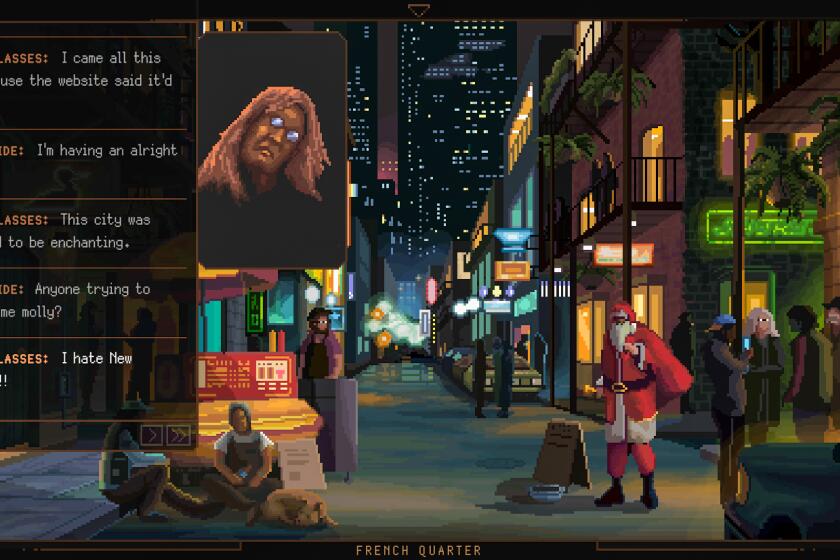

War exists for meme-making in ‘Norco.’ If you liked ‘Kentucky Route Zero,’ another game where we spend time with those on society’s outskirts, you may fall in love with ‘Norco.’

I sense “A Memoir Blue” is a game that will feel deeply personal to those who play it. The relationship drawn here is filled with unique details — we open as our protagonist is revealed to be a championship swimmer and seemingly lost in melancholic thought about winning. But without dialogue or text, “A Memoir Blue” relies solely on a mix of 3D and 2D animation, allowing us to graft any parent-like relationship onto it. On a simple level, it may prod you to call a loved one, but where “A Memoir Blue” excels is in using its magical realism to bring about contrasts, to show us, for instance, at once the wonder in urban construction lights and the loneliness of looking out onto an empty building.

When we see a city apartment, for instance, it’s equally claustrophobic and charming. We move through the story via the mind of a daughter, now grown, but in the game we are equally her mother. We feel the stress, the exhaustion and the isolation of adulthood as much as we do the yearning for companionship and the celebration of imagination that accompanies childhood. Ultimately, “A Memoir Blue” wants to meet us somewhere in the middle, to show that these affections fit together like puzzle pieces in a game that lacks them.

“A Memoir Blue,” published by Annapurna Interactive, the game division offshoot of the film and television studio, and developed by the small Cloisters Interactive team led by Shelley Chen, is described as an “interactive poem.” That’s not inaccurate, and Chen told video game publication Polygon that she wanted the game to evoke the sensation that accompanies crying. Not necessarily the sadness, I don’t think, so much as the release, the realization, at long last, of seeing childhood through the eyes of an adult.

Games are particularly well suited to this sort of magical realism. While “A Memoir Blue” would work as a companion piece to, say, Disney/Pixar’s “Turning Red,” as both traffic in how familial bonds can become in and out of sync, our minds enter a state of curiousness when we know we can interact.

When we turn a coral reef into a symphony or move ice cubes to reveal bright orange saltwater fish in a drinking cup, we ourselves are entering a state of vulnerability. Games are often spoken of as putting a player in control — moving, fighting, shooting — but in games that lack such contrivances, we are surrendering control and letting the interactivity take us by the hand. In “A Memoir Blue,” we are simply uncovering memories, but as we ask ourselves how or why, the game becomes less about turning jellyfish into an orchestra (there’s a lot of music in the game) and more a prod to unbury our own obscured recollections.

One particular thoughtful scene starts with a boat ride and a broken bridge we reconstruct by dragging it back together. Here, the ocean is the sky, the water in the game forever obscuring the past and making us swim or dig through it to bring the hidden imagery back to the present. Once rebuilt, we see younger versions of mother and daughter, each at different turning points in their lives. There are always unknowns, of course, but if one sees adventure — the daughter is simply enchanted by the lights that surround the boat’s helm — another struggles just to ensure that reality doesn’t intrude on that spellbinding view of the world.

For “A Memoir Blue” is primarily a study on the sacrifices we make that often go unseen. The game doesn’t linger on a breakup or the challenges of being a single parent; instead, it shows us new apartments blanketed with neon lights that materialize on the ocean floor. We see the mother’s late nights in the office and the child’s after-school hours in the pool, but we’re sometimes left to wonder just who is doing what for whom. Does swimming, for instance, truly make the young girl happy?

This isn’t a question “A Memoir Blue” wants to solve. Shortly after that boat ride, we’re re-creating footsteps and descending an escalator in a now-abandoned aquarium. It isn’t long before we’re underwater again and running or swimming to the next memory, our adult 3D woman often looking at her 2D child self with inquisitiveness. The game doesn’t prompt us to pause, but you likely will anyway. What we see when we swipe away one algae-concealed recollection after another isn’t so much an interactive poem as it is a thank-you card, one dedicated to all those who simply did the best they could for someone they loved.

'A Memoir Blue'

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.