Is hydrogen a climate savior or a disaster? Cutting through the hype

- Share via

This is the March 24, 2022, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

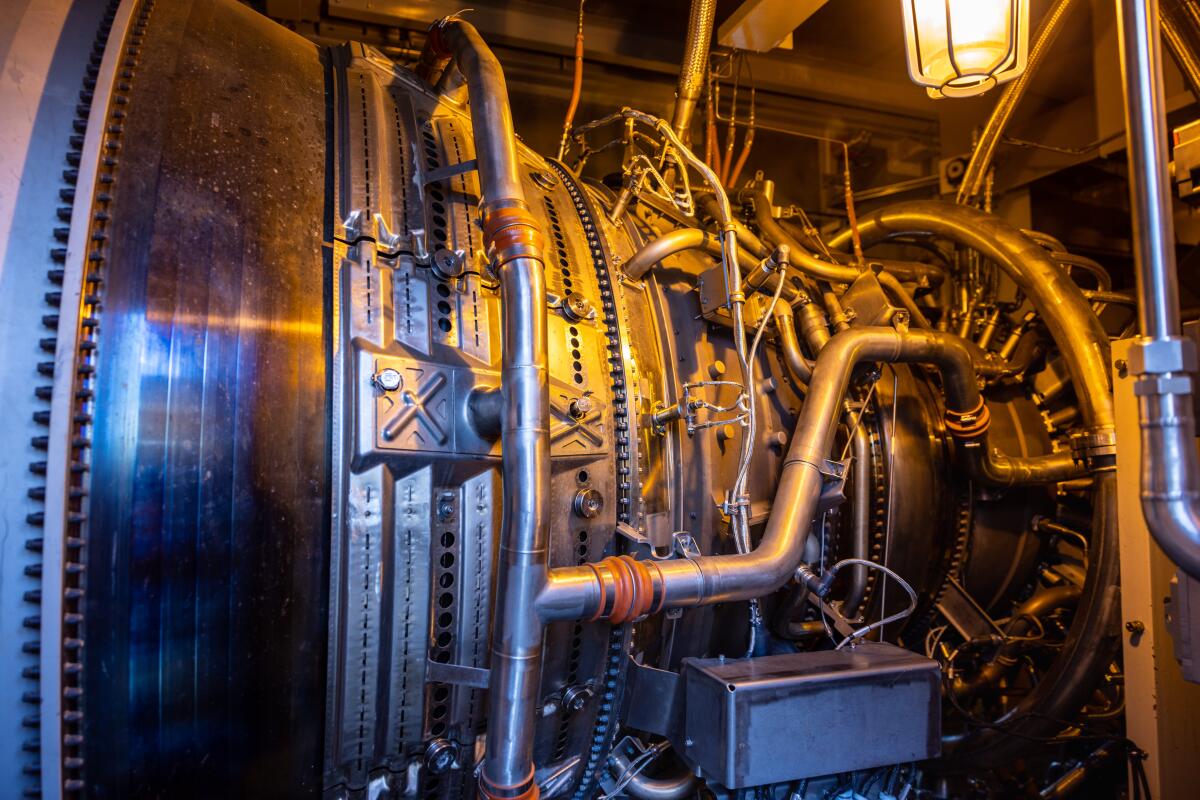

As I admired the beach views from Scattergood Generating Station — a sprawling mess of electrical wires, gas-fired generators and towering red-and-white smokestacks — I couldn’t stop thinking about how this power plant could never get built today.

It’s one of the largest electricity sources for the city of Los Angeles, and for 64 years it’s taken up a prime piece of coastal real estate just south of LAX. The plant sucks up ocean water to cool some of its machinery, killing fish and other marine life. It spews climate-disrupting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere and lung-damaging pollution into the air that Angelenos breathe.

Scattergood is a relic of a fossil fuel era that needs to end. But could it also serve as a foundation of the clean energy future?

The answer depends on your view of hydrogen — a fuel touted by fossil fuel companies (and some environmentalists) as a crucial tool for fighting the climate crisis, but derided by skeptics as the oil and gas industry’s latest greenwashing propaganda.

To help parse fact from fiction, I wrote this week about hydrogen, focusing on Southern California Gas Co.’s plan to build hundreds of miles of pipeline to bring the fuel to the Los Angeles Basin, including power plants such as Scattergood. Read the story and let me know what you think — and if you want The Times to keep investing in this kind of journalism, please consider subscribing.

“We’re the largest manufacturing center in the country, and we have the two largest ports,” SoCalGas President Maryam Brown told me. “You have a lot of those kinds of industrial end uses that need a clean fuel solution like hydrogen.”

There’s no doubt the world needs clean fuels — and many energy experts think hydrogen could be one of them. The European Union announced plans this month to dramatically increase its use of hydrogen by 2030, to help reduce dependence on Russian gas exports. The consulting firm Wood Mackenzie projects that hydrogen will account for 7% of global energy demand by 2050.

But as with almost every technology purporting to be a climate solution, there are obstacles and potential downsides.

With hydrogen, the first thing to know is that not all of it is “green.”

The vast majority of hydrogen in use today is “gray,” meaning it’s produced from fossil fuels in a highly polluting process. Then there’s “blue” hydrogen, made the same way as the gray stuff but with carbon-capture technology to stop planet-warming emissions from getting into the atmosphere. There’s been a lot of hype in the fossil fuel industry around blue hydrogen, although researchers have found it might end up being worse for the climate than fossil natural gas, at least under some circumstances.

Green hydrogen — the kind the L.A. Department of Water and Power wants to burn at Scattergood and other power plants, and the kind SoCalGas has promised to deliver — is produced from water and clean electricity sources, such as solar or wind, in a process called electrolysis. The electricity is used to split water molecules into their constituent parts, hydrogen and oxygen.

So green hydrogen is good and everyone supports it, right?

Big surprise, it’s not that simple.

As I detailed in my story, even green hydrogen generates smog-forming pollution when combusted, a problem that needs to be resolved if DWP and others want to keep producing electricity in the low-income communities of color where power plants are so often located. Skeptics also have questions about the fuel’s water use and indirect climate impacts — and the risk of explosions. Hydrogen is safer than fossil gas in some ways, but it’s also highly flammable, meaning pipeline leaks must be carefully managed.

Another consideration is that making green hydrogen isn’t exactly efficient. Think about it: We’re going to use clean electricity to produce hydrogen that will then be burned to produce electricity? Some industries may need hydrogen, but others can use solar or wind power directly — such as electric cars for transportation or electric heat pumps for home heating. Climate activists say we ought to “electrify” as much of the economy as possible, and only then turn to clean fuels to fill in the gaps.

This is a major point of contention between climate activists and SoCalGas. The company envisions supplying green hydrogen not only for power plants, the ports, long-distance trucks and heavy industry, but also potentially for home heating and cooking.

The gas company has also made big investments in biofuels sourced from landfills, wastewater treatment plants and massive dairy farms — an environmentally controversial effort that got a boost last month when the California Public Utilities Commission approved its first-ever regulation requiring gas utilities to source about 12% of their fuel from non-fossil sources by 2030.

“We see a wide range of fuels, including renewable natural gas and hydrogen, being a part of our strategic focus,” Brown said.

But climate activists say SoCalGas will need to accept a future where it’s delivering far less fuel to homes and businesses, as a growing number of local governments ban gas hookups in new buildings. Los Angeles could soon adopt its own requirement for newly built homes to be all-electric or otherwise zero-emission, under a City Council motion that I plan to write about soon.

Although activists see some value in hydrogen and biofuels, the gas company’s statements “make it seem as if they can transition their full customer base to alternative fuels,” said Tim O’Connor, an attorney at the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund.

“There’s a lack of reality that is embedded within that, when you look at the move toward broad-scale electrification,” he said.

SoCalGas seems to know it has a trust deficit to bridge with customers, state officials and clean energy advocates. So the company has linked its hydrogen pipeline proposal to a tantalizing prospect: the possible closure of its Aliso Canyon gas storage field, which sprung a record-breaking methane leak that sickened thousands of people in 2015 and 2016.

Residents of L.A.’s Porter Ranch neighborhood have been working for years to shut down Aliso Canyon, without success. A bill from state Sen. Henry Stern (D-Los Angeles) would require SoCalGas to close the facility by 2027, but it’s far from clear whether the legislation will pass. And although the Public Utilities Commission has been studying the facility’s closure for years, the agency’s president, Alice Reynolds, told me earlier this month that Aliso still plays a key role in meeting energy demand in the L.A. Basin.

“What we’ve found in initial modeling is that it is needed for California,” Reynolds said.

SoCalGas has never shown a public willingness to shut down Aliso Canyon — until now. The hydrogen transported through the company’s proposed “Angeles Link” pipelines could help replace the fossil gas currently stored at Aliso, Brown told me.

“Angeles Link, together with other clean energy investments, we think will help facilitate the closure of Aliso Canyon,” she said.

The environmentalists I asked about this were intrigued but skeptical. What if SoCalGas were to get approval to spend billions of ratepayer dollars building hydrogen pipelines, only to change course on Aliso and insist that the facility was still needed?

That skepticism stems in part from the gas company’s history of fighting climate action — a history that resulted in a $10-million fine from the Public Utilities Commission last month. When I asked Reynolds, the agency’s president, whether she sees SoCalGas as more of a roadblock or a partner in confronting climate change, she responded, “We will need everybody playing a role.”

“I’m hopeful that SoCalGas will be a good partner. They have some new management,” Reynolds said. “I’m going to be continuing to look for positive steps from them, as well as making sure we’re using our enforcement authority when needed.”

Similar stories are playing out across the country as fossil fuel companies scramble to secure their place in the energy transition. SoCalGas is the nation’s largest gas utility, but it’s just one of many companies making the case that hydrogen and biofuels can play a key role in zeroing out planet-warming emissions. The American Gas Assn., an industry trade group, released a report last month arguing that pipelines and other gas infrastructure will be crucial for transporting and storing clean fuels.

Los Angeles, meanwhile, is just one of several places looking to win a share of $8 billion in federal “hydrogen hub” money that the Biden administration is preparing to distribute. The governors of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming — two Democrats and two Republicans — are making plans to apply for some of the funds, as is a coalition of Arkansas, Louisiana and Oklahoma.

Here in California, Gov. Gavin Newsom hopes to allocate $100 million in state funds for green hydrogen. That money could support L.A. and neighboring Glendale, where city officials have been talking up hydrogen as a possible solution to their own gas plant.

That talk is cold comfort to the Sierra Club, which sued Glendale this month over its decision to “repower” the plant with new gas generators. Glendale City Council delayed a final decision on spending $260 million to buy five new gas engines but otherwise voted to move forward with the project — a move the Sierra Club argues violates the California Environmental Quality Act.

“Residents deserve a firm commitment from Glendale City Council for non-combustion,” said Monica Embrey, who leads the Sierra Club’s California energy campaigns. “Knowing that technology could be used that would dramatically increase asthma and respiratory disease is not acceptable, especially when we have clean energy options that are proven and can keep our lights on.”

All of which brings me back to Scattergood Generating Station, along the beach near El Segundo.

It’s one of three gas plants L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti promised in 2019 to shut down. Now DWP wants to convert the plants to green hydrogen instead. But what if hydrogen doesn’t pan out, and Los Angeles is forced to keep burning gas to keep the lights on?

Garcetti told me he’s optimistic about hydrogen. But he also realizes it’s no sure bet.

“If technology gets you to zero-emission gases like green hydrogen, and it actually is viable and it works, then that’s worth exploring. I don’t think any community or any climate activist would ever oppose that,” he said. “But let’s see the proof in the pudding first. Let’s not just add a drop of a clean gas to justify the continued burning of more destructive ones.”

Again — read my full story on the promise and perils of green hydrogen, and let me know what you think. And subscribe to The Times to support our climate journalism. I’ll have more reporting on this topic in the weeks and months to come.

Until then, here’s what’s happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

A proposed ocean wind farm off Central California is facing opposition from conservationists and tribal leaders, who say it would mar the proposed Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary. “Our histories begin and end on this coastline for time immemorial,” Sage Walker, chair of the Northern Chumash Tribe, told my colleague Louis Sahagún. This is just one of many renewable energy projects facing environmental opposition, including a San Diego County solar farm battling a California Environmental Quality Act lawsuit from unhappy residents of a small tourist town, as Rob Nikolewski reports for the San Diego Union-Tribune. Speaking of CEQA, there’s growing debate over the landmark environmental law, which critics say could impede the construction of clean energy projects and public transit needed to fight climate change, The Times’ Liam Dillon writes.

Limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius will likely require rich countries to end oil and gas production by 2034. That’s according to a new report out of the University of Manchester, as explained by Maxine Joselow at the Washington Post. In California’s Kern County, though, local leaders hope to ramp up fossil fuel drilling to help replace Russian oil, The Times’ Louis Sahagún reports. Whether they succeed may depend on the outcome of several court battles, including Chevron’s lawsuit against Gov. Gavin Newsom over the state’s denial of fracking permits and a separate case brought by environmentalists (both stories by John Cox at the Bakersfield Californian). The Biden administration, meanwhile, says it will resume federal oil and gas leasing — but that’s not likely to help combat Russia or reduce gasoline prices, Jonathan P. Thompson writes in his Land Desk newsletter.

California is reevaluating its cap-and-trade program — but while it does, people of color will continue to breathe polluted air in the shadow of oil refineries. My colleague Jonah Valdez talked with residents of L.A.’s Wilmington neighborhood, which hugs the fence line of the Phillips 66 refinery, about cap and trade. The program is supposed to help address climate change, but critics say it has allowed fossil fuel companies to keep polluting with impunity. In the meantime, the Golden State hasn’t passed major climate legislation since 2018, which is one reason California Environmental Voters — formerly known as the California League of Conservation Voters — just gave the state a “D” on its annual scorecard, Liza Gross reports for Inside Climate News.

WATER IN THE WEST

California is slashing State Water Project allocations from 15% to 5% as drought deepens — but still not mandating water conservation. Here’s the story from The Times’ Hayley Smith. State officials are also warning 20,000 water rights holders along the Sacramento, San Joaquin and other rivers to prepare for cutbacks, per Ryan Sabalow and Dale Kasler at the Sacramento Bee. In related news, plans for a new reservoir that would draw water from the Sacramento River just got a big boost from the federal government, which indicated it would give the Sites project a $2.2-billion loan, the AP’s Adam Beam reports. All this is coming against a backdrop of worsening drought conditions expected across the West this spring, as my colleague Paul Duginksi reports.

On the all-important Colorado River, some scientists say Western states should plan for no more than 11 million acre-feet of water annually, instead of the long-promised 15 million. But it’s politically fraught, with Arizona’s water boss quipping at a Utah conference that he won’t say 11 million “because I might get arrested when I get off the plane in Phoenix,” as the Arizona Republic’s Brandon Loomis reports. Meanwhile, new research shows that Lake Powell — the Colorado’s second-largest reservoir — is not only dropping due to drought but has also lost 6.8% of its storage capacity to sediment buildup over the years, Brian Maffly reports for the Salt Lake Tribune. And lest anyone think the Colorado is the only Western river causing political headaches, the Wall Street Journal’s Joe Barrett wrote about the states of Colorado and Nebraska squabbling over the South Platte.

California is once again trying to limit chromium-6 contamination in drinking water — to 10 parts per billion, 500 times more than scientists say is needed to limit cancer risk. No one is especially happy about this, with public health experts and activists, including Erin Brockovich, saying the new regulation is wildly insufficient and water utilities saying it will lead to higher monthly bills, as Rachel Becker writes for CalMatters. The state’s last attempt to regulate chromium-6 was thrown out in court.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

Gasoline now costs nearly $6 a gallon on average in California, throwing politicians into crisis mode. Ten Democrats and one independent in the state Legislature want to give $400 rebates to every taxpayer to defray the rising costs of gas and other goods, my colleagues Phil Willon and John Myers report; U.S. Sen Alex Padilla plans to co-sponsor a bill that would tax large oil companies and return the money to taxpayers, as John notes in a column on the perilous politics of high gas prices. Gov. Gavin Newsom entered the fray Wednesday with his own proposal of tax refunds for car owners and grant funding for free public transit, Taryn Luna reports. It’s fascinating to me how many of California’s existential questions are reflected in this debate — namely housing, income inequality and climate change, as seen in this story by Mackenzie Mays on who should be eligible for a gas-tax rebate.

A labor dispute could lead to even higher gasoline prices if a Bay Area oil refinery is forced to shut down, which thus far it hasn’t. KQED’s Ted Goldberg wrote about the strike at Chevron’s Richmond refinery, which has seen 500 steelworkers walk off the job in a dispute over safety and pay, fueled partly by the Bay Area’s high cost of living. This weird gas-price moment is also a good opportunity to look back at the bizarre stuff some Angelenos did when gasoline was in short supply in the 1970s, such as hijacking an oil tanker at gunpoint and offering bribes to cut ahead in lengthy gas-station lines, as Times columnist Patt Morrison writes.

As I’ve written previously, energy experts say the only way to truly insulate the U.S. from oil-market shocks is to use less oil — and California’s Antelope Valley is showing one way to do that. Canary Media’s Julian Spector explains how Antelope Valley Transit Authority — at the western edge of the Mojave Desert in northern Los Angeles County — became the nation’s first transit agency to fully electrify its bus fleet, with help from a local electric bus factory. For the Golden State to accommodate tens of millions of electric vehicles, it will almost certainly need more power lines. That helps explain why the California Independent System Operator just approved nearly $3 billion worth of transmission projects, as Kavya Balaraman reports for Utility Dive.

AROUND THE WEST

The California desert is a lot more fragile than it appears. Just look to Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, where climate change is drying up crucial wetlands and threatening iconic plants and wildlife, including fan palms and bighorn sheep, as Joshua Emerson Smith reports for the San Diego Union-Tribune, with gorgeous photos by Ana Ramirez. These kinds of climate impacts are why many scientists have called for the U.S. to protect 30% of its lands and waters by 2030 — a goal that Gov. Gavin Newsom hopes to accelerate by giving $100 million to tribal nations to help them buy back ancestral territory, as Maya Yang writes for the Guardian.

Sixty-eight percent of Bureau of Land Management staffers who responded to an internal survey say the federal agency should do more to combat climate change. Scott Streater of E&E News wrote about the survey, which could have important implications for an agency that has long focused on resource extraction. In other public-lands news, the National Park Service booted a dozen people from their trailer-park homes just outside Yosemite, saying deteriorating power lines posed an unacceptable fire hazard. The Park Service plans to repurpose the site as a campground, my colleague Nathan Solis reports.

The U.S. Forest Service can’t hire enough firefighters to keep up with climate-fueled blazes in the West, and it’s no secret why — relatively low pay and a lack of affordable housing across the region. Politico’s Ximena Bustillo has the details, based on internal Forest Service communications. In other not-great wildfire news, Bob Berwyn reports for Inside Climate News on new research finding that smoke columns can rise into the stratosphere and deplete the ozone layer, adding to skin cancer risk.

ONE MORE THING

Longtime Boiling Point readers will know that in addition to being an energy nerd, I’m a pretty big Disney fan. So imagine my surprise while watching the 1990s cult classic “A Goofy Movie” for the first time this week to discover all sorts of energy details embedded in the film. The plot centered around a musician named “Powerline” with an atomic-energy logo, and there were a bunch of background shots of energy infrastructure, including power plants, transmission lines, oil derricks and a windmill.

I shared some of those images on Twitter and asked the movie’s director how all the energy stuff came to be. No reply as yet.

In other cinema news, here’s the wild story of how AMC — yes, the movie theater company — decided to buy a 22% stake in the owner of a Nevada gold and silver mine that was almost out of money, courtesy of Reuters’ Mike Spector and Anirban Sen.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.