Nigerian Cyber Scammers

- Share via

FESTAC, Nigeria — As patient as fishermen, the young men toil day and night, trawling for replies to the e-mails they shoot to strangers half a world away.

Most recipients hit delete, delete, delete, delete without ever opening the messages that urge them to claim the untold riches of a long-lost deceased second cousin, and the messages that offer millions of dollars to help smuggle loot stolen by a corrupt Nigerian official into a U.S. account.

But the few who actually reply make this a tempting and lucrative business for the boys of Festac, a neighborhood of Lagos at the center of the cyber-scam universe. The targets are called maghas — scammer slang from a Yoruba word meaning fool, and refers to gullible white people.

Samuel is 19, handsome, bright, well-dressed and ambitious. He has a special flair for computers. Until he quit the game last year, he was one of Festac’s best-known cyber-scam champions.

Like nearly everyone here, he is desperate to escape the run-down, teeming streets, the grimy buildings, the broken refrigerators stacked outside, the strings of wet washing. It’s the kind of place where plainclothes police prowl the streets extorting bribes, where mobs burn thieves to death for stealing a cellphone, and where some people paint “This House Is Not For Sale” in big letters on their homes, in case someone posing as the owner tries to put it on the market.

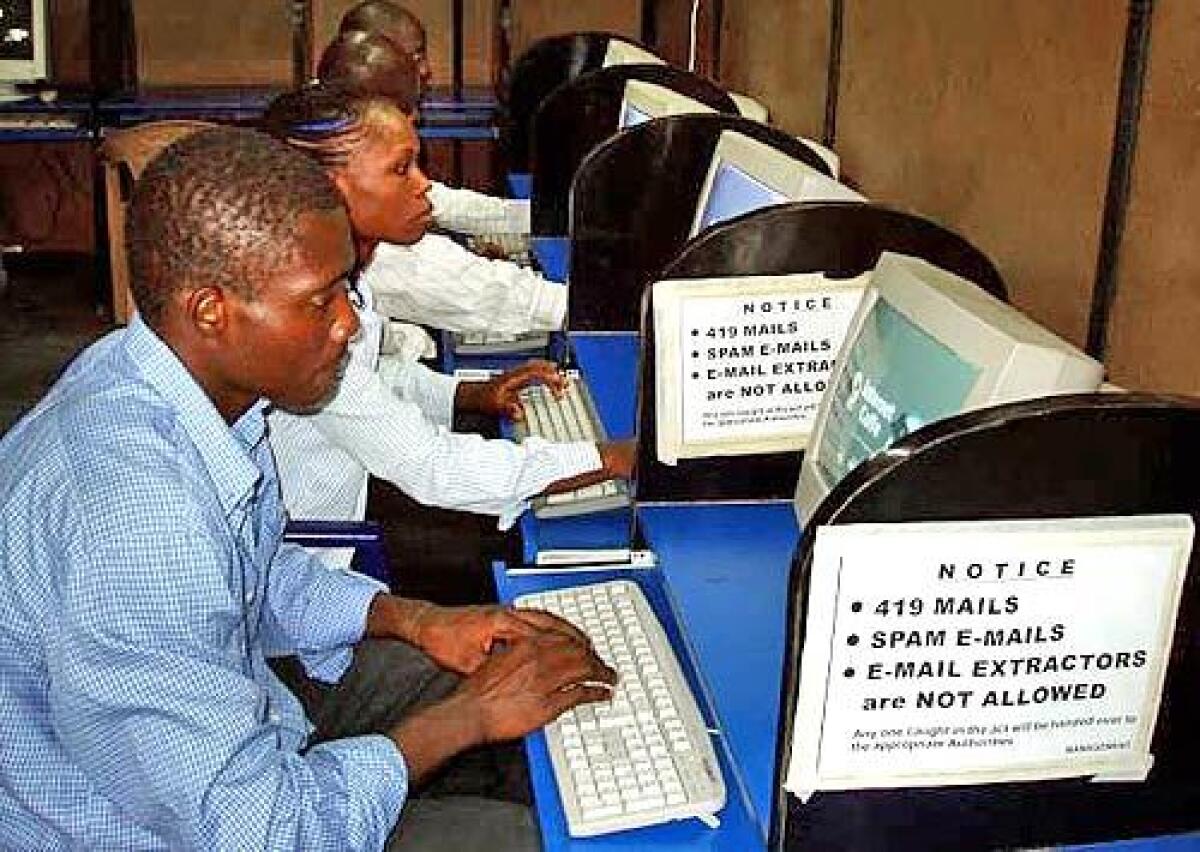

It is where places like the Net Express cyber cafe thrive.

The atmosphere of silent concentration inside the cafe is absolute, strangely reminiscent of a university library before exams. Except, that is, for the odd guffaw or cheer. The doors are locked from 10:30 p.m. until 7 a.m., so the cyber thieves can work in peace without fear of armed intruders.

In this sanctum, Samuel says, he extracted thousands of American e-mail addresses, sent off thousands of fraudulent letters, and waited for replies. He thinks disclosure of his surname could endanger his safety.

The e-mail scammers here prefer hitting Americans, whom they see as rich and easy to fool. They rationalize the crime by telling themselves there are no real victims: Maghas are avaricious and complicit.

To them, the scams, called 419 after the Nigerian statute against fraud, are a game.

Their anthem, “I Go Chop Your Dollars,” hugely popular in Lagos, hit the airwaves a few months ago as a CD penned by an artist called Osofia:

“419 is just a game, you are the losers, we are the winners.

White people are greedy, I can say they are greedy

White men, I will eat your dollars, will take your money and disappear.

419 is just a game, we are the masters, you are the losers.”

“Nobody feels sorry for the victims,” Samuel said.

Scammers, he said, “have the belief that white men are stupid and greedy. They say the American guy has a good life. There’s this belief that for every dollar they lose, the American government will pay them back in some way.”

What makes the scams so tempting for the targets is that they promise a tantalizing escape from the mundane disappointments of life. The scams offer fabulous riches or the love of your life, but first the magha has to send a series of escalating fees and payments. In a dating scam, for instance, the fraudsters send pictures taken from modeling websites.

“Is the girl in these pictures really you?? I just can’t get over your beauty!!!! I can’t believe my luck!!!!!!!” one hapless American wrote recently to a scammer seeking $1,200.

The scammer replied, “Would you send the money this week so I may buy a ticket?”

“Aww babe. I don’t have the money yet. I will get it, though. Don’t you worry your pretty lil head, hun,” the victim wrote back.

The real push comes when the fictional girlfriend or fiancee, who claims to be in America, goes to Nigeria for business. In a series of “mishaps,” her wallet is stolen and she is held hostage by the hotel owner until she can come up with hundreds of dollars for the bill. She needs a new airline ticket, has to bribe churlish customs officials and gets caught. Finally, she needs a hefty get-out-of-jail bribe.

The U.S. Secret Service estimates such schemes net hundreds of millions of dollars annually worldwide, with many victims too afraid or embarrassed to report their losses.

Basil Udotai of the government’s Nigerian Cybercrime Working Group said 419 fraud represents a tiny portion of Nigerian computer crime, but is taken seriously by authorities because of the damage it does to the country’s reputation.

“The government is not just sitting on its hands,” he said. “It’s very important for the international community to know that Nigeria is not glossing over the problem of 419. We are putting together measures that will tackle all forms of online crime and give law enforcement agencies opportunities to combat it.”

“He’s fun to be with. When you’re around him he makes you feel you have no problems,” Samuel said. Shepherd hooked him with the same bait he uses for maghas.

“He said every hour I spent online I could be making good money,” Samuel recalled. “He said, ‘The houses I own, I got it through all this.’ And they’re not just ordinary houses. They’re big, made of marble. He’s got big-screen TVs, a swimming pool inside. He lives like a prince. He’s the biggest guy in this town.”

A teenager who didn’t really know about the scams, Samuel was “a bit confused” when Shepherd offered him 20% of the take. “But I looked at everything he had, and it got into my head, actually. The money he had, the cars.”

Eager to impress his new boss, Samuel worked for six-hour stretches extracting e-mail addresses and sending off letters that had been composed by a college graduate also working for Shepherd.

He sent 500 e-mails a day and usually received about seven replies. Shepherd would then take over.

“When you get a reply, it’s 70% sure that you’ll get the money,” Samuel said.

Soon he was working for two bosses, Shepherd and Colosi, both well known to authorities but neither of them bothered in a place where police involvement in the scams is widely alleged.

“Most of the time you look for American contacts because of the value of the dollar, and because the fraudsters here have contacts in America who wrap up the job over there,” Samuel said. “For example, the offshore people will go to pose as the Nigerian ambassador to the U.S., or as government officials. They will show some documents: This has presidential backing, this has government backing. And you will be convinced because they will tell you in such a way that you won’t be able to say no.”

After a scam letter surfaced this summer bearing the forged signature of Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo, police raided a market in the Oluwole neighborhood of Lagos, one of six main centers that provide documents used in the 419 scams. They seized thousands of foreign and Nigerian passports, 10,000 blank British Airways tickets, 10,000 U.S. money orders, customs documents, fake university certificates, 500 printing plates and 500 computers. A stolen U.S. passport fetches $2,500 on the black market here.

The scams often involve bogus Internet sites, such as lottery websites, or oil company, bank or government sites. The scammers sometimes use London phone prefixes to make victims think they are calling Britain.

Though the fraud is apparent to many, some people think they have stumbled on a once-in-a-lifetime deal, and scammers can string them along for months with mythical difficulties. Some victims eventually contribute huge sums of money to save the deal when it is suddenly “at risk.”

Stephen Kovacsics of American Citizen Services, an office of the U.S. Consulate, spoke to a victim who had lost $200,000.

Kovacsics says he is awakened several nights a week by Americans pleading for help with an emergency, such as a fiancee (whom they have only met in an online chat room) locked up in a Nigerian jail. He has to tell them that there is probably no fiancee, no emergency.

Kovacsics said victims can’t believe that a scammer would spend months of internet chat just to net $700 or $1,000, not realizing that is big money in Nigeria and fraudsters will have many scams running at the same time.

By 2003, Shepherd was fleecing 25 to 40 victims a month, Samuel said. Samuel never got the 20%, but still made a minimum of $900 a month, three times the average income here. At times, he made $6,000 to $7,000 a month.

Samuel said Shepherd employs seven Nigerians in America, including one in the San Francisco Bay Area, to spy on maghas and threaten any who get cold feet. If a big deal is going off track, he calls in all seven.

“They’re all graduates and very smart,” Samuel said. “Four of them are graduates in psychology here in Nigeria. If the white guy is getting suspicious, he’ll call them all in and say, ‘Can you finish this off for me?’

“They’ll try to scare you that you’re not going to get out of it. Or you’re going to be arrested and you will face trial in Nigeria. They’ll say: ‘We know you were at Wal-Mart yesterday. We know the D.A. He’s our friend.’ ”

“They’ll tell you that you are in too deep — you either complete it or you’ll be killed.”

Samuel said his mother, widowed when he was 16, was devastated when she saw him in the street with Shepherd and realized what he was up to.

“She tried to force me to stop, but the more force she applied, the more hardened I became. I said: ‘You can’t give me what I want. I want a good life.’ ”

But Samuel began having second thoughts when a friend was arrested after ripping off a boss for $17,000.

The friend was badly beaten before disappearing into the depths of the labyrinthine Nigerian justice system. Samuel thought of his mother and how she would be left alone if something happened to him.

When he gave up cyber crime at the end of last year, he said nothing to his mother. But she noticed.

“She said she was happy and she could sleep well,” he said. “Actually, I started crying. I couldn’t control myself. I realized there was more to life than chasing money.”

Now when he sees Shepherd in the streets, his former boss just grins.

“He says: ‘Don’t worry. You’ll come back to me.’ ”

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

The many forms of 419 scams

Advance-fee frauds, also known as 419, appear to offer a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to get rich or find the girl of your dreams. The scams can involve phony websites, forged documents and Nigerians in America posing as government officials. Here are some of the most popular:

The “next of kin” scam, tempting you to claim an inheritance of millions of dollars in a Nigerian bank belonging to a long-lost relative, then collecting money for various bank and transfer fees.

The “laundering crooked money” scam, in which you are promised a large commission on a multibillion-dollar fortune, persuaded to open an account, contribute funds and sometimes even travel to Nigeria.

The “Nigerian National Petroleum Co.” scam, in which the scammer offers cheap crude oil, then demands money for commissions and bribes.

The “overpayment” scam, in which fraudsters send a bank check overpaying for a car or other goods by many thousands of dollars, persuading the victim to transfer the difference back to Nigeria.

The “job offer you can’t refuse” scam, in which an “oil company” offers a job with an overly attractive salary and conditions (in one example, $180,000 a year and $300 per hour for overtime) and extracts money for visas, permits and other fees.

The “winning ticket in a lottery you never entered” scam — including, lately, the State Department’s green card lottery.

The “gorgeous person in trouble” scam, in which scammers in chat rooms and on Christian dating sites pose as beautiful American or Nigerian women, luring lonely men into Internet intimacy over weeks or months then asking them to send money to get them out of trouble.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.