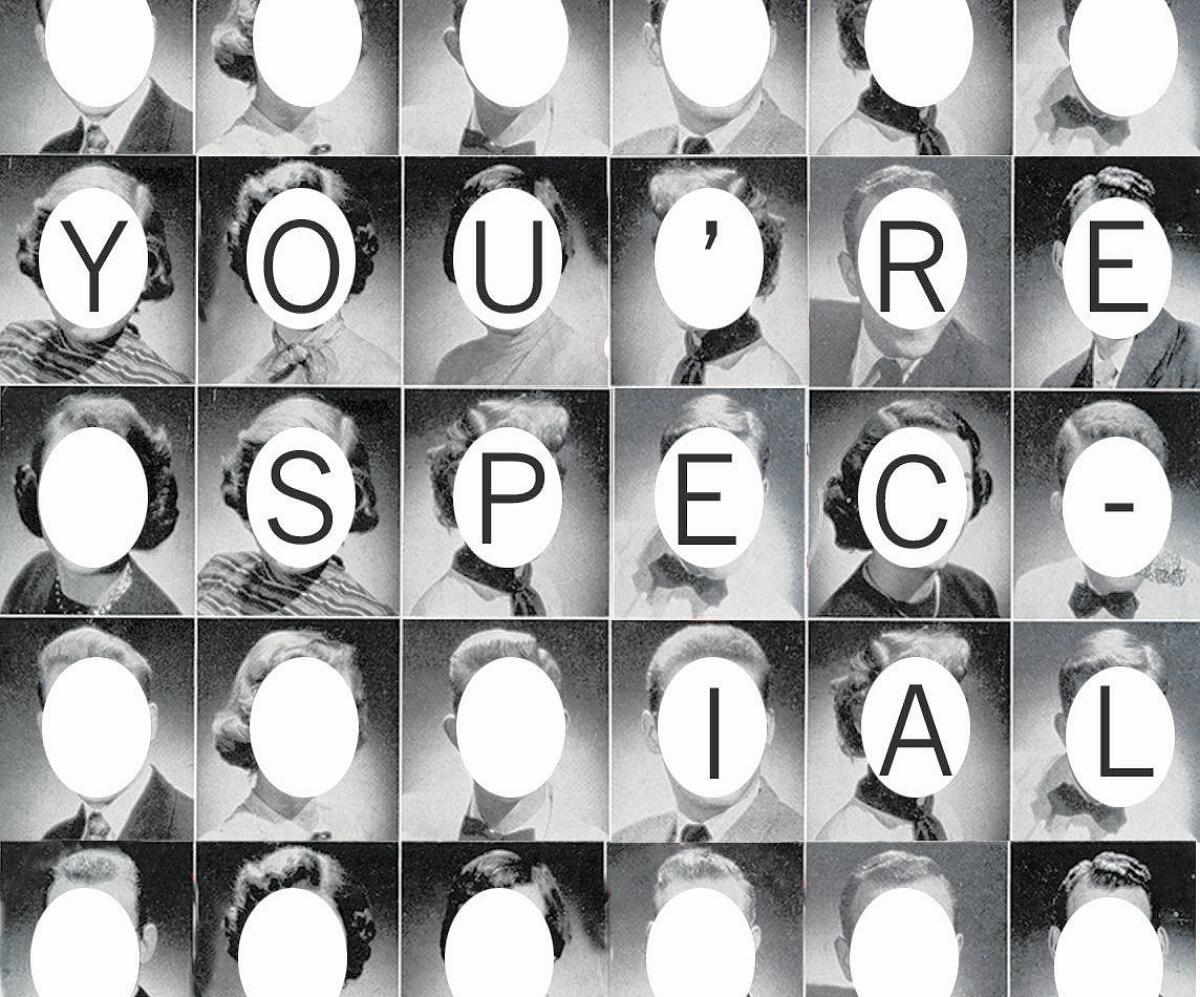

Op-Ed: Victims of confidence schemes have something in common: They think they’re special

- Share via

A few years ago, an internationally respected 68-year-old physicist fell for a sweetheart scam. Paul Frampton met a young supermodel online, became convinced he was corresponding with the new love of his life and traveled to La Paz, Bolivia, to meet her. By the time Frampton arrived, the supermodel had been called away to a photo shoot in Brussels, but she left behind a black bag that she said had “sentimental value.” He checked the bag at the airport on the way home — and ended up in jail for drug smuggling. The bag was lined with cocaine.

After Frampton was imprisoned, he said he was unlike the other inmates: Unlike them, he was innocent. “I think people like me are less than 1%,” he said. It was a characteristic statement. He once told a reporter that his Oxford grades showed that, like Isaac Newton, he was in the top 1% for intelligence.

All sorts of people fall for confidence schemes. Smart people. Rich people. Skeptical people. (And their counterparts: Dumb, poor or gullible people.) What ties them together? Like Frampton, they think they’re special. They go about their lives convinced they’re unlike everyone else.

****

We’ve all heard the adage, “If it seems too good to be true, it probably is.” But when evaluating the opportunities that come our way, many of us latch on to that “probably” and add a little twist: “If it seems too good to be true, it probably is — unless it’s happening to me, because I’m extraordinary.”

With nary an exception, we don’t recognize that we’re ordinary; most of us think we’re above average — which means most, if not all of us, are potential scam victims.

David Modic, a psychologist at the University of Cambridge’s Computer Laboratory and at King’s College, explains how belief in one’s superiority effectively nullifies common sense. “Prospective scam victims,” he writes, “might overestimate their ability to detect fraud, both because they, on average, think that they are better at detecting fraud than they actually are and because they think they are more in control of the situation than they actually are.”

Overconfidence leads them to believe they couldn’t possibly have misjudged a situation or a person, which makes them reject as impossible the reality that they’ve been had.

Similarly, the Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman has found that illusions of superiority make people underestimate the likelihood of negative outcomes. Those who suffer from the better-than-average effect, or the Lake Wobegon effect — it goes by many names — take riskier gambles and stay in iffy situations far longer than others, failing to sense danger. They’re also more likely to “underestimate the role of chance in human affairs and to misperceive games of chance as games of skill.”

If an ordinary billiards player who recognizes she’s an ordinary billiards player walks into a bar, is invited to shoot pool, and wins the first three rounds easily, she might suspect a trap when she’s asked to play double or nothing. But an ordinary billiards player who thinks she’s exceptional might not notice anything unusual about her string of good luck. It’s not even luck, she tells herself, it’s skill.

Here’s the thing: With nary an exception, we don’t recognize that we’re ordinary; most of us think we’re above average — which means most, if not all of us, are potential scam victims.

Of one million students who took the SATs in 1976, 70% thought they were above average in leadership ability and 60% in athletic ability. Roughly 85% of students put themselves above the average in their ability to get along with others. In 1977, a full 95% of the faculty of the University of Nebraska thought they were better than average at teaching; more than two-thirds placed themselves in the top quarter. In a survey that behavioral economist Richard Thaler performed on his students, he found that less than 5% of the class expected to do below average, and over half thought they would be among the top fifth of performers.

Of course we’re all better-than-average drivers, far more skillful than the next guy. In one study, researchers asked drivers who had been hospitalized after a car accident — which more than two-thirds of them had caused — to rate their driving skills. They said they were better than average at exactly the same rate as drivers who had no accident history.

Often harmless, vanity can lead to victimization. The confidence artist will do everything in his power to bring our better-than-averageness front and center. Grifters appeal to our pride, not about just anything, but about the things that are most central for us. And we believe their praise. Not because it’s plausible but because we want it to be. The more exceptional we see ourselves, the easier we are to con.

****

Frampton’s supermodel was deft: She recognized how highly he valued his intellect, and she appealed to that. She was done with average people. She needed someone of his intellectual caliber, someone she could really spend time with, who would appreciate everything about her and not just her looks. She may have been extraordinary — but so was he.

The list of victims blinded by egotism is long. Another recent example comes from France: Two con artists convinced a wealthy family of aristocratic descent that they were the targets of a massive plot perpetrated by “sinister” forces that included the Freemasons. Eventually, 11 family members, spanning three generations, handed over $6 million in assets, the 300-year-old family estate and countless personal items to the grifters. How could such a sophisticated family swallow such a tall tale? Thierry Tilly, the plot’s main perpetrator, knew they were proud of their heritage — the family’s friends often said as much — and so used it as an entry point. It was an extraordinary story — but they, after all, were extraordinary people. It made sense that they’d find themselves at the center of a global conspiracy.

As one grifter — a player of the short con known as the tat — told David Maurer, an early historian of the con, “A New Yorker is the best sucker that ever was born. He is made to order for anything. You can’t knock him. He loves to be taken because he’s wise.” Because New Yorkers fancy themselves so cosmopolitan and sophisticated, they are the easiest fish to catch. (Angelenos, presumably, would be exempt from this criticism.)

As long as we keep thinking ourselves exceptional, we will continue to be potential victims, and the con will continue to thrive. And who honestly wants to go through life admitting to being average — or worse?

Maria Konnikova is the author of “The Confidence Game: Why We Fall For It…Every Time” and a contributing writer for The New Yorker.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.