Column: After Derek Chauvin, the culture of law enforcement needs to go on trial

- Share via

After Friday’s sentencing of Derek Chauvin, I saw a sign that hit me pretty hard: “One down three to go.”

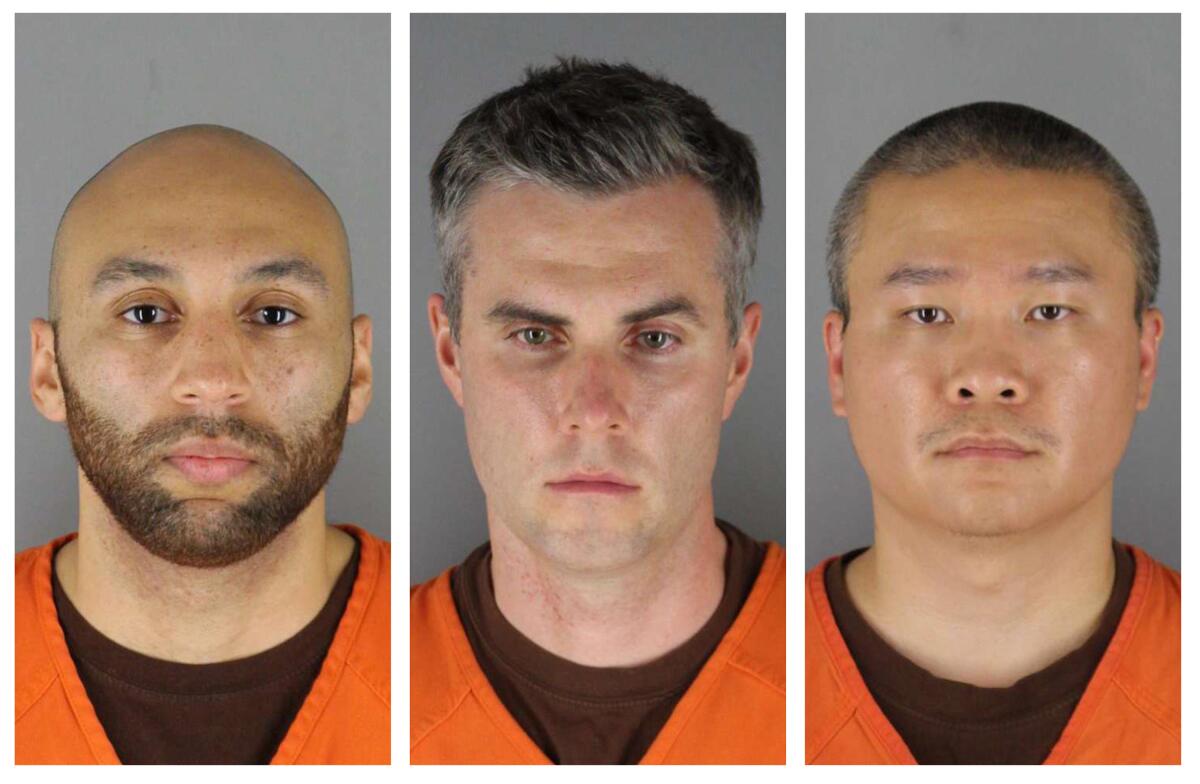

It was a reminder that the former police officer who received 22½ years for killing George Floyd wasn’t alone that day. A reminder that three other officers — Thomas Lane, J. Alexander Kueng and Tou Thao — are charged with aiding and abetting second-degree murder and manslaughter. That Chauvin’s conviction was the easier part.

After all, he’s the one on camera with his knee on Floyd’s neck. He’s the one other officers had no problem taking the stand against because his actions clearly were in violation of their training. He’s a “bad apple,” as they like to say.

But here’s the messy part: Lane and Kueng, who are seen on the video holding Floyd down, were rookies. Thao, Chauvin’s partner, stood between them and the onlookers begging the officers to stop. Chauvin, a 19-year veteran on the force, was the senior officer at the scene.

So the question is, will law enforcement officials who testified against Chauvin be as willing to testify against three officers who were following the chain of command as well as the “cops don’t rat out cops“ unofficial rule ?

It won’t just be the three officers on trial but the culture of law enforcement itself.

To understand just how pervasive this unspoken rule is, take the circumstances surrounding the 2014 murder of 17-year-old Laquan McDonald. We were told the teen lunged at officers with a knife and that they had no choice but to shoot. The video, which the mayor’s office tried to keep secret, revealed not only that McDonald was walking away from police before shots rang out, but also that he fell to the ground after the first shot. Didn’t matter. Over the course of 14 seconds, Officer Jason Van Dyke shot McDonald 16 times, nine in the back. The shooting happened in October. The district attorney obtained the video a few weeks later, but Van Dyke wasn’t arrested until more than a year later. Until a court ruled the video had to be made public.

And none of that is the most disturbing part.

No, the most disturbing part is that at least 16 officers were involved in the cover-up. And unlike Chauvin, Van Dyke wasn’t even the most senior officer on the scene. Yet all those Chicago police officers participated in protecting this man — some of whom actually watched him empty his clip into a lifeless teenage body right in front of them.

There are other examples of this blue wall of silence, of course — the contradiction between the Louisiana State Police report and the scenes captured in the body cam video of Ronald Greene, a motorist who died after he was arrested, comes to mind.

And there are examples we may never know about because body cameras weren’t turned on. Sometimes all of the cameras fall off at the same time, which is what three police officers in Aurora, Colo., said happened after an alleged physical altercation with Elijah McClain, a 5-foot-6, 140-pound massage therapist, who died after being put into a chokehold during a police stop in 2019.

Chauvin? He’s low-hanging fruit.

A bad apple.

The initial Minneapolis Police Department statement made no mention of what that bad apple had done to George Floyd in front of a crowd, but it did say Floyd may have been on drugs.

The Times reported that John Elder, the department’s spokesman, said he got his information from sergeants who were in the area. Who gave the sergeants that information? It wouldn’t appear to have been from any of the witnesses begging for George Floyd’s life. One would think if “man dies” is in the headline of a police statement, a knee on said man’s neck for more than nine minutes would have been important to include.

Chauvin?

His conviction was historic but not a litmus test.

The true test is what happens to the three officers who should have saved Floyd’s life, because that speaks to the very heart of the issue when it comes to criminal justice.

It’s not about the training or the body cams. It’s not about distancing yourself from or embracing calls to “defund the police.”

Those are important matters to be sure, but until there is trust none of those other things matter. That’s what at stake here — trust.

That “One down, three to go” sign I saw was about so much more than the officers involved in Floyd’s death. It’s about those good apples we keep hearing about but who don’t always show up when a man is gasping for air, begging for his life.

It’s about the good apples whose response to seeing an officer shoot a teenage boy nine times in the back was to protect the officer. That mentality, that blue wall of silence is what the three officers are on trial for and by extension every officer who ever witnessed improper conduct and chose to be quiet.

@LZGranderson

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.