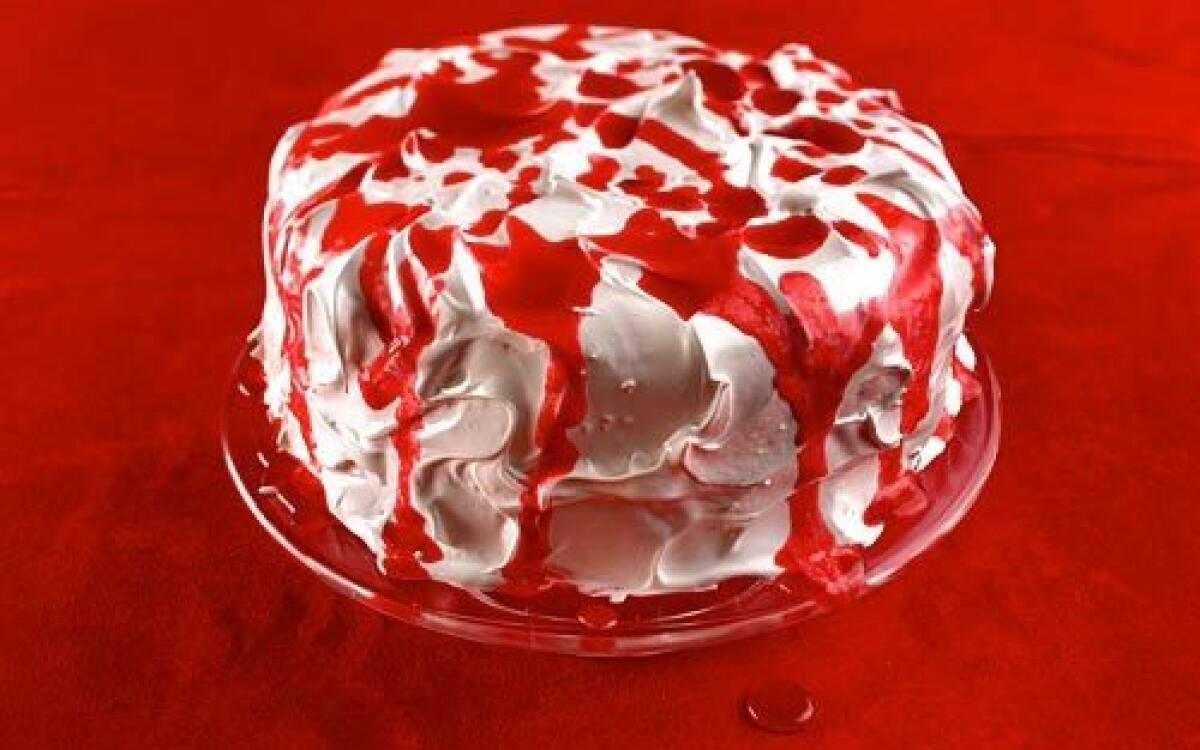

Raspberry crime scene cake

- Share via

A cookbook can change your life. Two years ago I reviewed one called “Southern Cakes,” which did just that.

Like most people, I’d always thought making a cake from scratch was only for the heroic. In fact, Nancie McDermott’s book showed me that all you have to do is beat butter and sugar to a cream, beat in some eggs and add flour and milk in alternating batches, and there’s your batter.

Wow, really have to lie down and recover after all that.

I’m a different person now. People see me and say, “Hey, Cake Guy!” Because I’m usually carrying a cake around with a goofy grin on my face.

Once I’d grasped the basics (and tried just about every recipe in “Southern Cakes”), I moved on to Rose Levy Beranbaum’s “The Cake Bible,” and “The Art of the Cake” by her mentors Bruce Healy and Paul Bugat. Both books are crammed with sophisticated techniques, and I now follow Beranbaum’s foolproof method of making butter cream frosting. Her discussion of the chemistry and physics behind her recipes is invaluable.

But many of the cakes in Beranbaum’s book don’t tempt me, and none of those in Healy and Bugat’s do. Namely, the classic French bakery cakes.

French cakes are impressive-looking, but they strike me as chilly and fussy.

And they use a lot of ingredients that leave me cold -- spun sugar, marzipan, kirsch, candied fruit, chestnut puree (sorry, but I think of it as a kind of porridge). Gack. And look at all the stuff they leave out. There’s not a single coconut cake in “The Art of the Cake”!

The French idea of frosting basically seems to be something that lies flat so you can decorate it. They have no use for our unruly American frostings -- no cream cheese frosting, no good old American seven-minute icing. And all that piped frosting they do -- forget it. In my book, real men don’t know a star tip from a drop flower tip.

Though we got cake making from the French, we Americans have created our own repertoire. Notably, we make our cakes light with the use of baking powder (French cakes are mostly leavened with beaten egg white), so our cakes tend to be taller. French cakes are usually little short one-layer jobs anyway, and any cake under 4 inches high just makes me sad. The high egg-white content of French cakes makes a lot of them dry and chewy, so they have to be soaked with syrup before being frosted.

The French approach has been taken to an extreme by Charm City Cakes, the wild Baltimore bakery featured on the Food Network’s “Ace of Cakes.”

Though I appreciate the cleverness and skill and all-around wackiness, I watch the show pretty much the way I watch shows about people erecting bridges over dangerous gorges. I never think of their cakes as, you know, food. All that fondant icing, which is nothing but sugar syrup boiled to the consistency of putty; all that gum paste and royal icing, which are just structural elements. As chef Michel Richard has observed, they don’t seem to be cakes for eating but for looking at.

Here are the steps on my way to becoming the Cake Guy. Pay attention. This could happen to you.

First, I bought some good 9-inch pans, and I started keeping fresh baking powder on hand. Freshness makes a big difference in everything connected with cake.

Then I started hanging out at restaurant supply places. I invested $4.50 in a package of 100 (9-inch) parchment paper circles; totally worth it -- butter your pans, then put in the parchment paper and butter it, dust everything with flour, and your cake will always come out of the pan in one piece, no matter how delicate the batter.

I found a little cake tester for $2.50 and some long, narrow spatulas for frosting. OK, the angled spatula was $12, which seemed steep, but it works better in close quarters. I bought a round French cake rack, which is very useful for transferring a cake layer from its pan to a cooling rack, though I was starting to run out of space in my kitchen.

I bought this thing to wrap around my cake pans so the layers would bake up with a flatter surface, though I’ve hardly ever used it.

Pretty soon I couldn’t pass a restaurant supply place. One day I was a little early on my way downtown, so I stopped off at Surfas in Culver City, telling myself it was just to kill 15 minutes. First thing I knew I’d bought a small food mill. Well, it is handy if you’re making a quantity of fruit puree too small to be done in a food processor.

A couple of days later I picked up a sugar sprinkler, a little worried that this might be a utensil too far. When I bought a package of 50 (10-inch) cardboard cake rounds (essential for carrying a cake to somebody else’s house), I realized that cakes were kind of taking over my life.

But I don’t care. I’m Mr. Popularity now. I’m the Cake Guy.

As Easy As 1, 2, 3, 4

Your basic American yellow cake is made from flour, sweetened with sugar, given structure with eggs, enriched and tenderized with butter, leavened with baking powder and flavored with vanilla and a little salt. You may have all the ingredients to make a cake on hand right now.

The most common recipe is known as 1-2-3-4 cake, because it uses 1 cup each of milk and butter (that’s two sticks of butter), 2 cups of sugar, 3 cups of flour and 4 eggs. (Actually, it also needs one-half teaspoon salt, 1 teaspoon vanilla and 2 teaspoons of baking powder, so I suppose it’s really the 1-2-3-4 plus 1/2 -1-2 cake.)

The usual technique starts by creaming the butter and sugar -- a complicated, impressive, highly technical process that consist of putting both ingredients in the mixer on high speed for maybe two minu tes (the butter should be at room temperature, neither cold nor melted). Then you add the eggs one by one and beat for a minute or two. Wow, how hard was that?

Finally, you mix the flour with the baking powder and salt in one bowl, and add the vanilla to the milk in another, and slowly beat both mixtures into the butter and egg mixture, alternating the flour and milk, just until the flour is incorporated.

For a lighter texture, many recipes add the yolks to the batter separate from the whites, which are beaten and folded into the batter after the flour (I rarely bother). Other recipes mix the sugar with the flour and add the butter, eggs and milk to it, or mix the sugar with the eggs first before beating in the rest. However you do it, the liquid should always be added to the flour last and the batter should be mixed just until the flour is absorbed.

If you’ve turned your oven to 350 degrees, you’re now half an hour away from having a couple of cake layers. As soon as they’re cool, you can frost them and bask in glory.

Heat the oven to 350 degrees. Generously grease the interior of two 9-inch round cake pans, both bottom and sides, with butter. If possible, line the bottom of each pan with a 9-inch round of parchment or wax paper and grease it also.

Sprinkle about 2 teaspoons flour into each pan and shake around until each interior is thoroughly dusted. Turn the pans upside down over the sink and tap against the sink to dislodge any excess flour.

In a medium mixing bowl, stir 3 cups flour with the baking powder and salt and set aside. In a measuring cup or small bowl, combine the milk with the vanilla and set aside.

In the bowl of a stand mixer, or in a large bowl using an electric mixer, beat the 1 cup butter until fluffy, 1 to 2 minutes.

Reduce the speed and add the sugar with the mixer running, continuing to mix until light and fluffy, 2 to 3 minutes more. Add the eggs one at a time and beat into the mixture.

Add one-third of the milk mixture and beat until absorbed. Add one third of the flour mixture and beat just until the flour is absorbed. Repeat with the remaining milk and flour in two batches.

Divide the batter between the two cake pans and smooth the tops with a spatula. Bake the cakes in the center of the oven until the tops are golden brown and the cake starts to pull away from the sides of pan, 25 to 35 minutes.

Remove the cake pans from the oven and set on a cooling rack or folded towel for 10 minutes. Overturn the cake pans onto a rack or plate, remove the pans and paper from them and return the layers, right-side up, to the rack or towel. Wait to frost the cakes until they have cooled to room temperature.

Raspberry crime scene frosting and final assembly

Puree the raspberries in a food processor and force through a strainer to remove the seeds. This should make about one-half cup raspberry puree. Stir in 6 tablespoons sugar until dissolved and set aside.

In a medium bowl, combine the remaining sugar, corn syrup and water mixture, egg whites, salt and cream of tartar. Beat the contents with a hand-held electric mixer until lightly foamy and pale yellow, about 1 minute.

Place the bowl over a larger pot of simmering water (making sure the bottom of the bowl does not touch the water). Continue to beat the mixture to achieve a puffed and billowy white meringue (the meringue will practically reach the top of the mixer blades), 8 to 10 minutes. Continue beating until the mixture holds stiff peaks and just begins to lose its gloss, 1 to 2 minutes more.

Remove the bowl from the pot of simmering water and add the vanilla. Beat one additional minute to fully incorporate the vanilla.

Assemble the cake: Put one cake layer, top side down, on a serving plate or stand. Cover the top with about one-third of the frosting, then drizzle over one-third of the raspberry puree. Set the second layer, top-side up, over the first. Frost the top and sides of the cake with the remaining frosting, and drizzle over the remaining raspberry glaze. Serve immediately.

Get our Cooking newsletter.

Your roundup of inspiring recipes and kitchen tricks.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.