Leukemia drug treats MS, even when others fail

- Share via

A drug now used to treat leukemia was successful in treating relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, beating out the primary MS drug, interferon beta 1a, in two clinical trials reported Wednesday. The drug was also more effective in treating patients who had failed treatment with current drugs. The new drug, called alemtuzumab, could be approved for marketing as early as this year. The drug has some relatively severe side effects, but clinicians are confident those can be controlled with careful monitoring of patients. Many physicians have already been prescribing the drug to their patients, but the outcome of the new trials has been widely anticipated.

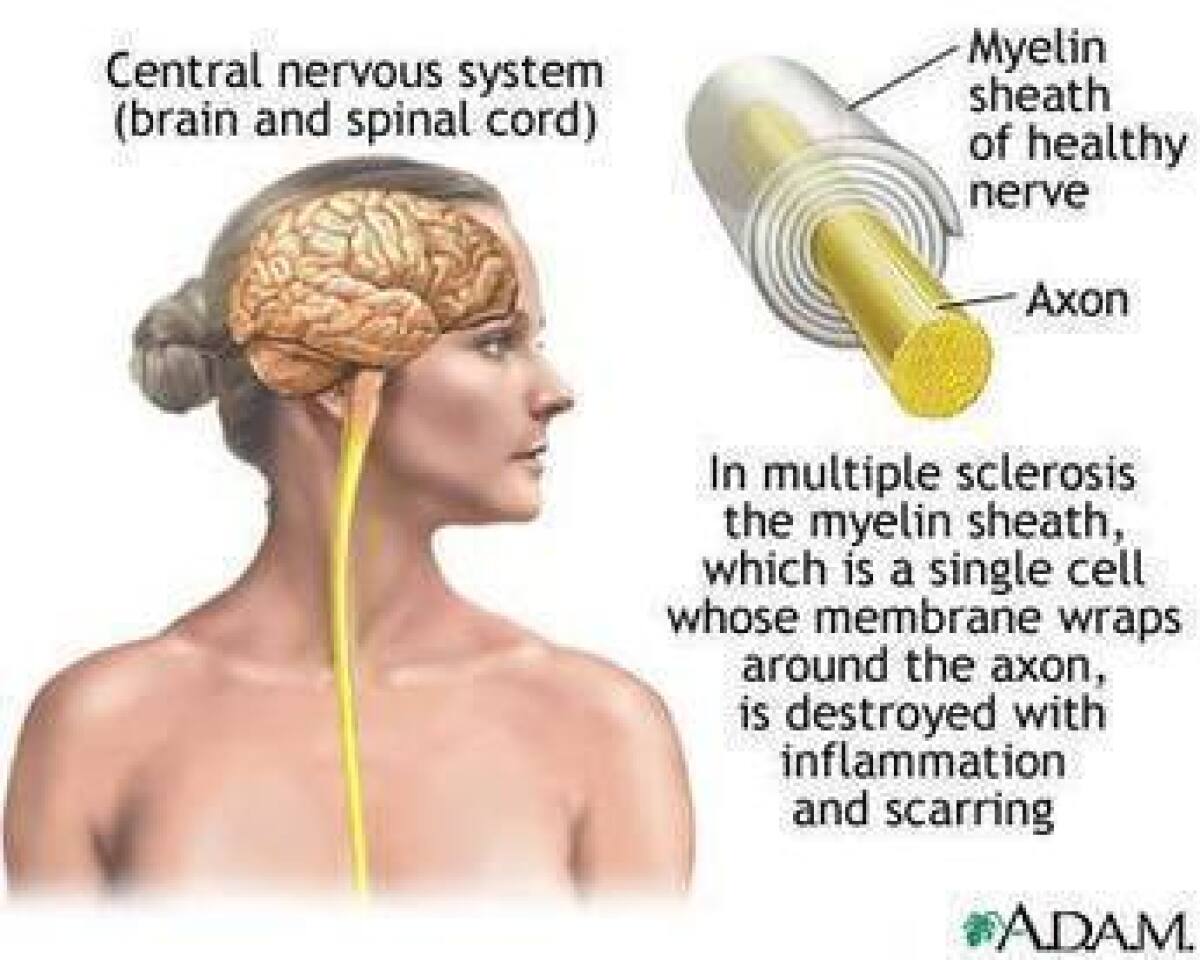

Multiple sclerosis affects about 400,000 people in the United States. The precise cause is not known, but symptoms occur when the body’s immune system attacks the myelin sheaths surrounding nerves -- in effect, short-circuiting the nerves. Characteristic symptoms include impairments of vision, movement, balance, sensation, bladder control and, eventually, memory and cognition. In the relapsing-remitting form, symptoms appear sporadically, then fade away, either partially or completely. There is no cure for the disease.

Two teams of researchers, each headed by Dr. Alastair Compston of the University of Cambridge, conducted separate two-year clinical trials of the drug, the results of which were reported Wednesday in the medical journal Lancet. In one trial, called CARE MS I, researchers compared alemtuzumab to inteferon beta 1a, the primary existing treatment for MS, in 563 patients who had not yet received any treatment for the disease. About 40% of patients who received interferon relapsed within two years, compared with 22% of those who received the new drug.

In the second trial, called CARE MS II, researchers compared the same two drugs in 628 patients who had been treated with either interferon or glatiramer, another MS drug, but suffered a relapse. In this group, 51% of patients receiving interferon suffered another relapse, compared with 35% of patients receiving alemtuzumab. Also in this trial, 20% of patients receiving interferon showed an accumulation of new disabilities during the two years of the trial, compared with13% of those receiving the new drug. In CARE MS I, there was no statistically different accumulation of disabilities in the two groups.

The primary side effects of the drug were inflammation at the infusion site, thyroid autoimmunity and immune throbocytopenia, a decrease in blood platelets. Both illnesses are treatable if detected early. Some data indicate that it may be possible to identify people who are most susceptible to these side effects, according to Dr. Alasdair Coles of Cambridge, a lead author on one of the studies. Studies are now underway to attempt to identify these susceptible individuals, as well as studies in which a novel drug is given in conjunction with alemtuzumab to block their development.

The drug has been marketed by Genzyme (a Sanofi company) under the brand name Campath for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and T-cell lymphomas. The company is applying for permission to market it for MS under the brand name Lemtrada. According to an editorial by the editors of the Lancet, the company has withdrawn the drug from the U.S. and British markets in anticipation of that approval. The editors expressed concern that the withdrawal would prevent patients who are already being treated with it from receiving the drug and that the new version of the product might be too expensive for patients and insurers.