In South Africa, continuing racism leads blacks to doubt Mandela’s vision

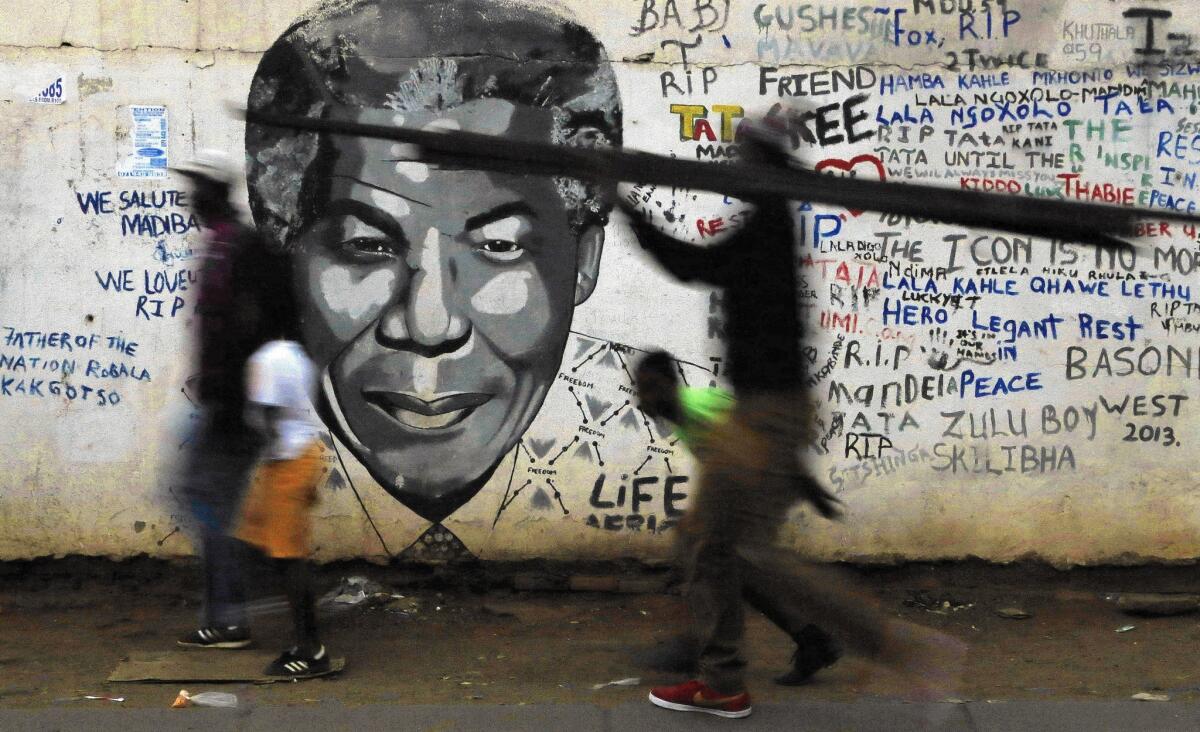

A Nelson Mandela mural in Katlehong, south of Johannesburg, South Africa.

- Share via

reporting from Johannesburg, South Africa — Early one weekend morning, just after the nightclubs had closed, three young white men ambled into the harsh fluorescent light of a South African takeout food franchise. They whistled at the staffers, all of them black, tugged their clothing and pulled their caps askew. When customers Sikhulekile Duma and two fellow black students told them to stop, they said people who didn’t speak Afrikaans didn’t belong there.

“They were whistling at them like they were whistling [at] dogs. They even jumped over the counter and they were patting them like they were dogs. Yourself, you feel disrespected. You know this is racial, this disrespect,” Duma said.

After leaving the restaurant in Stellenbosch, near Cape Town, Duma and his friends were confronted by seven young white men, including the three who had humiliated the staff.

“These guys were really big. I got hit from behind and I fell on the ground. My glasses broke,” Duma recalled in an interview about the February incident.

Racist incidents such as this, Duma says, remain commonplace in South Africa more than two decades after Nelson Mandela, the nation’s first black president, took office.

At Stellenbosch University, Duma is a member of an activist group seeking to make the overwhelmingly white governing council more representative, to demand that it offer all classes in English and to reform the “passively hostile culture of white Afrikanerdom.”

After organizing a protest last month at the inauguration of the university’s new rector, who is white, Duma received a text message: “Jou swart moer van die wit boer” — “You black bastard from a white farmer.”

A white academic at the university has been suspended, pending an investigation, on suspicion of sending the message.

Reports of racism have increased at universities, schools, parking lots, restaurants and office blocks, and on Facebook and Twitter, according to the South African Human Rights Commission. Some black South Africans, frustrated by overt racism, question Mandela’s soft vision of reconciliation.

There have been reports of a Pretoria school segregating classes based on race; an office building in Limpopo province with a whites-only toilet; and a fancy Cape Town restaurant that refused a caller a reservation once he gave his last name, Mpofu, which identified him as black.

Other racial incidents in recent months have included the Tasering of a woman in a fight over a parking space by a woman who allegedly first intoned a racial epithet; and an assault on a black woman by a white man who said he thought she was a prostitute.

And then there was the Afrikaner singer Sunette Bridges, who wrote on Facebook that the only way to get a black construction worker to build straight was to use a whip. She later said that the comments were in jest and that she didn’t even know what it meant to be racist.

One of the more shocking recent incidents involved white students at a boarding school in the town of Jan Kempdorp stripping a black student, tying him to a bed, lathering him with shampoo and raping him, according to South African news reports. Police confirmed the attack, which took place weeks after the ringleader harassed the black student for having dated a white girl.

Black activists say other examples of racism are more subtle, and thus insidious, such as a reluctance to allow blacks into elite restaurants or the strange looks they get in shopping malls or while walking in wealthy neighborhoods.

Tumi Mpofu and her family say they were denied a reservation at an upscale Cape Town restaurant, the 12 Apostles, last year after her father provided their surname. When Mpofu then asked a white friend to phone for a table of the same size a few minutes later, the request was granted.

When the Mpofu family arrived, they were told there was no table. Again Mpofu phoned her white friend, who intervened, and the Mpofus were seated. Restaurant management acknowledged making a mistake but denied racism.

“Our words just seemed to fly right past them,” Tumi Mpofu said. “There were six adults. It had to take a white person who was not even in the same room for them to take us seriously. This incident was just so upsetting for me and obviously hurtful.”

Once seated, “it took us forever to get someone to come to us. On top of everything that happened, they came and told us to keep it down,” she said. “My dad was absolutely livid.”

Political power might have changed hands 21 years ago, but much of South Africa’s economic power remains in the hands of whites. White per capita income in 2008 was about $9,400, compared with $1,220 for blacks, according to the South African Institute of Race Relations.

Now that the first black president has passed away, many young black South Africans reject what some call “Mandela’s bubble” and believe that whites should give up their economic advantages to atone for the past. Many whites, comfortable and privileged, don’t see the need for a new debate on race. To them, it’s time blacks stop referring to the nation’s ugly apartheid past.

“It’s like an abuser telling the abused to get over it,” Mpofu said.

“Many whites in South Africa are generally unwilling to engage in the topic of racism — most crying out that we ‘must move beyond race’ and that they ‘do not see color,’” South African filmmaker and writer Gillian Schutte, who is white, wrote in a column in the Mail and Guardian newspaper. “This is the new phenomenon of ‘colorblind racism’ that denies and ignores the fact that for people of color/black people, race still matters because they still experience it.”

Anger over that attitude spills into newspaper columns about race. In 2011, black newspaper columnist Lerato Tshabalala penned a piece directed at whites to express “how intensely it bothers us when you grin, when you make eye contact with a black person. It makes us feel like you’re afraid we’ll take your wallet.... Just don’t grin. It’s not warm, it’s fake.”

“Dear White South Africans,” blogger Ntsiki Mazwai wrote in an angry polemic last year. “There are certain behaviors which provoke the hell out of Africans. Most of these issues are centered around your SELF importance. What is it about you white people that makes you think that your thoughts, ideas and existence [are] more important than other races?”

Verashni Pillay, a columnist with the Mail and Guardian, wrote in February that she was tired of talking about race, but “I wish every white person who thinks that race isn’t such a big issue and ‘we’re all just human’ could walk around as a black person for a day in a predominantly white area. You’ll have people cross the road to avoid you, or refuse to meet your eyes.

“You’ll have employers assume you’re lazy, forcing you to work harder than your white peers to prove otherwise. Restaurants and clubs may or may not give you good service but there’ll be a different awareness around your person, a bubble of air that will attract covert stares or animosity.”

Frans Cronje, chief executive of the South African Institute of Race Relations, said many South Africans assumed that more than two decades after Mandela was elected, racial tension in South Africa would have subsided. Instead, South Africa has become more divided, he said, as the economy has failed to deliver the growth and jobs required to bring greater financial equality.

“In a society that becomes increasingly polarized, you can expect more of these things coming to the fore,” he said, referring to the racist incidents. With South Africa’s growth predicted to be 2% this year, and the unemployment rate stubbornly high, the rand has declined, pessimism has set in, and Cronje expects “racial relations will be increasingly fraught and increasingly difficult.”

“We are starting to make peace with the fact that the inequalities we inherited from the apartheid era are going to be with us for very much longer than we imagined,” Cronje said.

As demands from black activists grew more insistent, he said, some whites reacted by circling the wagons.

“What that means is that policies of reconciliation or of bringing people together or of debate or discussion is going to be futile for South Africa, if at the same time we cannot ensure that the real telling experience in terms of living standards doesn’t improve.”

Duma, the Stellenbosch student, said the effect of apartheid remains ever present. “The fault lines have always been there and they have been deep and we have been quiet about it, and now we are getting to the point that it’s beginning to expose itself. What we are seeing is it’s not working. I think it’s to do with what a lot of white people have, in terms of white privilege,” he said.

Like Duma, Tumi Mpofu believes Mandela’s reconciliation has been too soft on whites.

“It’s all about accommodating white people and making them feel like they’re part of the new democratic South Africa, at the expense of black people. A whole lot of people are still holding on to this Rainbow Nation thing, because it benefits them because it’s working for them,” she said. “But it’s not working for black people.

“I don’t think our government has even begun to deal with racism issues. People are starting to wake up and say, ‘We’ve been deluding ourselves.’ The more racist incidents that happen, the more people are waking up.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.