He was accused of stealing millions and implicated in a deadly disaster. Now he’s a Mexican senator

- Share via

Reporting from Mexico City — In 2006, a methane explosion tore through the Pasta de Conchos coal mine in northern Mexico, killing 65 men toiling underground.

Some family members of the victims blamed the tragedy partly on Napoleon Gomez Urrutia, the leader of the country’s largest miners union, which less than two weeks before the accident had signed off on a government report that deemed the mine safe.

That same year, Gomez was accused by federal officials of pocketing tens of millions of dollars from a workers trust fund. He fled to Canada with his family and Interpol issued a warrant for his arrest. The embezzlement charges were dropped in 2014, but the twin scandals made Gomez a pariah in Mexican politics.

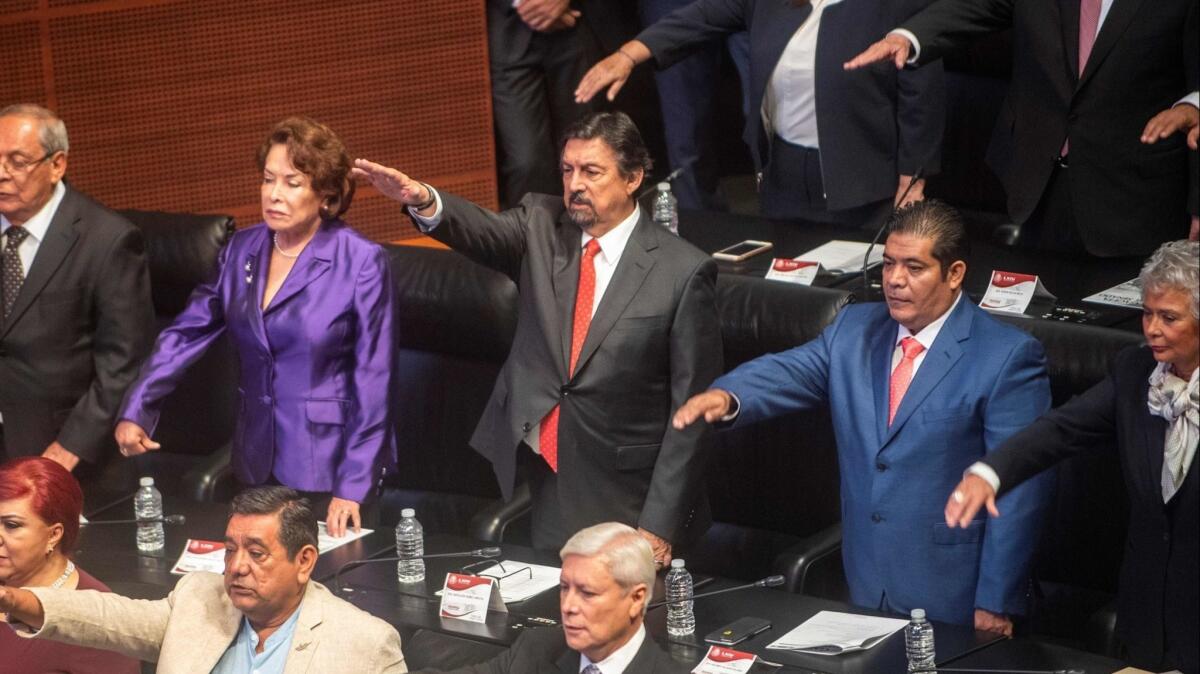

Which is why what happened this week was so improbable. Not only did Gomez return to Mexico after more than a decade in self-imposed exile, he was swiftly sworn in as one of the country’s newest senators.

His triumphant return was made possible by Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, the leftist politician who won July’s presidential election in a landslide.

Gomez, who had continued to lead the Mexican Union of Miners and Metalworkers, or Los Mineros, from abroad, had urged his group’s thousands of members to vote for Lopez Obrador.

In turn, Lopez Obrador promised to name Gomez as a lawmaker representing Morena, the political party he founded. (While most senators are elected by the public, some seats are reserved for political parties to distribute according to the votes the parties receive.)

Lopez Obrador defended his decision, saying the union boss had been exonerated of all charges and was the target of a smear campaign for taking on powerful mining companies. Gomez, Lopez Obrador wrote in a Facebook post earlier this year, “has been persecuted and stigmatized by official and unofficial propaganda.”

Lopez Obrador’s campaign was centered on his pledge to fight corruption and what he calls Mexico’s “mafia of power.” On the campaign trail, he proposed drafting a “moral constitution” to combat the well-documented greed of many of the country’s political and economic elite. To many critics, those promises don’t square with his appointment of Gomez.

“I don’t know whether to laugh or cry,” financial columnist Alberto Barranco wrote on Twitter after Gomez was sworn in to the Senate on Monday.

After Gomez pledged that “I am going to eliminate the country’s corruption,” he was widely mocked on social media.

But Gomez is not without his supporters.

On the day he was sworn in, thousands of union members, many of them in hard hats, gathered outside the Senate to show support for their beleaguered leader. Millionaire businessman Alfonso Romo, another Lopez Obrador backer, has compared Gomez and his exile to the confinement in prison of Nelson Mandela.

IndustriALL, an international federation of unions, issued a statement this week congratulating Gomez on his return home, saying that with him in the Senate, “Mexico’s new government is poised to overcome decades of corruption and corporate domination and make real improvements to the rights and living standards of Mexican workers.”

Gomez was a controversial figure even before the mine explosion. Some union members opposed his appointment as the group’s general secretary in 2002, when he succeeded his father who had held the position for four decades. They said Gomez, an Oxford-educated economist, was unqualified because he had never worked in a mine.

As union leader, many viewed Gomez as an advocate for miners and a thorn in the side of mine owners. He called multiple strikes to press for higher wages, drawing the ire of Grupo Mexico, the nation’s largest mining company.

But after the explosion, family members of victims complained that the union had suppressed worker complaints about safety. Gomez, meanwhile, blamed Grupo Mexico for allowing conditions that led to what he called “industrial homicide.”

At the same time, prosecutors pounced on Gomez for alleged embezzlement, arguing that he had pocketed $55 million in cash from a government settlement with the union meant for miners who lost jobs during the privatization of two mines. Gomez said the charges were part of a “witch hunt.”

While the charges against him were dropped, that did not erase many people’s doubts that Gomez may have indeed stolen money, said Sergio Aguayo, a human rights activist and academic in Mexico City. Mexico’s justice system is notoriously ineffective, and prosecutors are political appointees.

“Since we don’t have a judicial system that gets to the bottom of cases like this, one is always left with doubt about whether justice was served or if it was just another cases of cronyism,” Aguayo said. He called the decision to nominate Gomez to the Senate “a major question mark on Lopez Obrador’s commitment and capacity to radically transform Mexico’s political system.”

Aguayo said Lopez Obrador’s embrace of Gomez was a part of a larger campaign strategy to win the support of a wide array of interests, even if some of those interests may be in conflict.

Lopez Obrador, who previously ran for president and lost in 2006 and 2012, formed a coalition of diverse groups: leftist intellectuals, but also far-right evangelicals who oppose LGBTQ rights and old-time members of the long-ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party.

They helped win Lopez Obrador the election, but pose a challenge when it comes to governing. Gomez faces a different challenge — overcoming suspicions about his past.

At a news conference on Thursday, Gomez described his past problems as “an unjust, unnecessary, arbitrary conflict that was totally created by the groups of political and economic power that attacked me in order to destroy a union.”

“I am very happy to have led this fight,” he said.

Twitter: @katelinthicum

Cecilia Sanchez in the Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.