This tiny Utah town could shape the West’s energy future

- Share via

This is the May 19, 2022, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

The road to Delta is paved with pumpjacks and wind power.

Five days into our Western energy road trip, photographer Rob Gauthier and I drove late into the night across Utah, following the setting sun as it bathed the red-rock cliffs and snow-starved Wasatch Mountains in golden light. We crossed the Strawberry River — a sparkling tributary of the Colorado — before traversing Indian Canyon via Highway 191, a scenic byway lined with oil wells.

As sunset turned to dusk, we enjoyed sweeping views of Ashley National Forest from Indian Creek Pass, elevation 9,114 feet. An hour later, we passed the Beehive State’s first large wind farm, near the end of the sprawl that extends south from Salt Lake City.

By the time we reached Delta, population 3,600, it was well past dark, and I couldn’t see the massive smokestack north of town. It rises 710 feet from Intermountain Power Plant — a coal-fired plant that for decades has been L.A.’s largest electricity source.

That’s right, if you hadn’t gotten the memo: Roughly one-sixth of L.A.’s power comes from coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel.

Rob and I were following the planned route of a 732-mile electric line designed to bring wind power from Wyoming to California, and we had stopped in Delta primarily because the line will run through town. But we’d arranged a tour of the coal plant, too.

The last time I visited Intermountain, in 2019, L.A. officials were defending their plan to convert the plant to natural gas, a fossil fuel that’s less polluting than coal but still a major cause of the climate crisis. By the end of the year, though, they’d changed course, promising the rebuilt facility would run on 70% gas and 30% green hydrogen — and eventually 100% green hydrogen.

Nothing like that had ever been attempted before, and the energy analysts I talked with at the time were skeptical overall.

But a lot has changed since then — and I could see it from the roof of the power plant, the smokestack towering above.

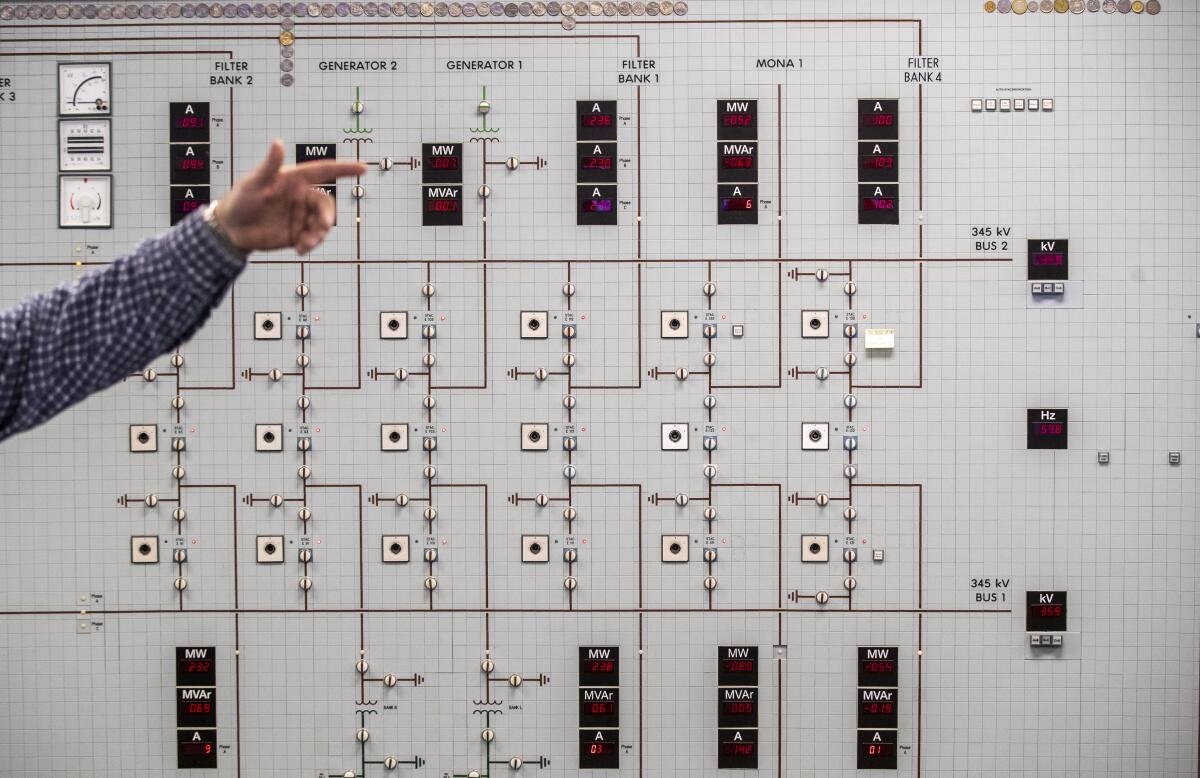

John Ward, a spokesperson for Intermountain Power Agency, pointed to several plots of land that will buzz with activity when major construction activities begin later this year. He told me the project would bring almost 1,000 workers to the site. Already, crews have been moving dirt to prepare for the installation of new turbines that can burn a combination of gas and hydrogen.

A few days after our visit, Ward’s agency sold nearly $800 million in municipal bonds to help finance the $1.9-billion project.

“This is absolutely on the world map,” Ward told me. “Everyone is paying attention to this.”

He wasn’t exaggerating. If all goes according to plan, Delta will be home to the world’s largest hydrogen-fueled generating station. The hydrogen will be produced via electrolysis, a pollution-free process that uses renewable energy to split water molecules.

Also key: the convenient presence of underground salt domes across the street from the plant, which can be used to store the fuel for months at a time. That means L.A. could produce green hydrogen on mild spring afternoons — when California often has more solar power than it can use — and combust the fuel on hot summer evenings, when keeping the lights on is increasingly difficult.

After returning home, I spoke with Rob Webster, co-founder of Magnum Development, the company that owns the salt domes and is developing hydrogen storage with Mitsubishi Power in a joint venture called ACES Delta. He told me the project offers several benefits that can’t be provided by lithium-ion batteries, another important tool that can bank clean electricity for after dark.

“A battery’s going to lose charge over time. And the big batteries are good for three to four hours. We’re storing this [energy] from spring until summer,” Webster said. “You can think about it like a battery, but it’s a whole different animal.”

There wasn’t much to see at Magnum’s property on a Saturday afternoon this month. When Ward led us through the gate across the street from the coal plant, two trailers were the only infrastructure in sight, part of a watering operation to keep down dust.

But when Rob sent up a drone, he spotted two neon-blue brine ponds just east of the site, built but no longer owned by Magnum. The company originally used the water to hollow out five underground caverns, pumping it into the salt dome and then bringing it back up — full of dissolved salt — and storing it in the ponds. The caverns are now used by Sawtooth Caverns, LLC, to store liquids including butane and propane, in a sort of proof of concept for what Magnum and Mitsubishi intend to do next with hydrogen.

The companies plan to build two hydrogen caverns and two salt ponds — at least initially. That should be enough to help Los Angeles reach its goal of a 70% gas/30% hydrogen fuel blend when the new power plant opens in 2025, Webster told me.

Each cavern will be roughly the size of the Empire State Building — only underground, and full of Earth’s lightest element.

“Storage provides a tremendous amount of flexibility,” Webster said. “It’s no different than the coal stockpile they have out back.”

To be clear, the project still faces uncertainties. Turbines capable of burning 100% hydrogen, for instance, don’t exist yet.

Another possible red flag involves Chevron. The fossil fuel giant said last year it would invest in the Magnum-Mitsubishi joint venture, with a Chevron spokesperson telling me the project “will be critical to delivering green hydrogen as a transportation fuel to California and other markets in the Western U.S.” But when I checked in with Chevron this week, another spokesperson told me the company never went through with the investment, saying the hydrogen project “no longer meets our requirements.”

The federal government, on the other hand, seems to think the project is worth dropping a bunch of money on. Last month, ACES Delta won a $504-million conditional loan guarantee, now in the process of being finalized, from the U.S. Department of Energy. The Houston-based private equity fund Haddington Ventures, which backs Magnum, is working to secure another $650 million.

By my count, that’s $3 billion or so that various parties expect to spend building the new plant, associated electrical infrastructure and hydrogen production and storage facilities. And it’s all predicated on L.A.’s commitment to 100% clean energy by 2035.

At the same time, what’s happening outside Delta is a lot bigger than Los Angeles.

Although the L.A. Department of Water and Power operates the coal plant — and the 488-mile transmission line that brings its electricity to Southern California — the infrastructure is owned by Intermountain Power Agency, a consortium of Utah municipalities. Several other California cities are involved, too, namely Anaheim, Burbank, Glendale, Pasadena and Riverside.

Ward has had a front-row view of the political disputes that have ensued, as L.A. made plans to stop burning coal and later decided fossil gas wasn’t a sustainable solution, either. The Utah Legislature hasn’t taken kindly to that clean energy transition, passing a bill last year punishing Intermountain Power Agency by stripping it of several privileges it had long enjoyed under state law.

But despite their political differences, the blue-state, red-state partners at Intermountain have thus far managed to keep working together. The California cities want clean energy, and their Utah counterparts want jobs and tax revenues.

“This has always been a remarkable project. You’ve got 30-plus partners from both ends of the political spectrum. And the way the governance of the project is set up, nothing happens unless both ends of the power line agree,” Ward told me. “The Californians can’t do things unilaterally, the Utahns can’t do things unilaterally. ... This is a poster child for interregional cooperation.”

That kind of cooperation will almost certainly be needed for California and other Western states to phase out fossil fuels. The Delta salt dome could potentially be a big part of that, storing hydrogen for use by trucks and heavy industry across the region.

Intermountain is part of a hydrogen renaissance fueled by climate ambitions. Companies have floated or announced hundreds of billions of dollars in investments the last few years, including a pipeline project pitched by Southern California Gas.

“Once we’re able to scale up, we’re going to find that the cost to produce hydrogen keeps on getting cheaper and cheaper,” said Bryan Fisher, a managing director at the think tank RMI, which researches and advocates for climate-friendly energy.

For all the hydrogen enthusiasm, there are still serious environmental concerns, including the potential for nasty smog-forming emissions during combustion, and the reality that most hydrogen in use today isn’t green but is instead made from fossil fuels.

So it’s not especially surprising that when Los Angeles City Council voted unanimously this week to apply for a share of $8 billion in federal hydrogen funds, some environmentalists, including the advocacy group Food & Water Watch, criticized the move.

“L.A. doesn’t need a hydrogen hub to advance our clean energy goals,” said Jasmin Vargas, the group’s senior L.A. organizer, in a written statement. “Cheaper, safer, less water intensive options exist right now and we should be looking to those.”

Other climate advocates are cautiously optimistic. And it’s not just Los Angeles interested in the federal hydrogen funds, which were included in the infrastructure bill signed by President Biden last year. Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration said Wednesday it would work with “public and private stakeholders,” including L.A., to submit a single funding application for the Golden State.

The federal money could help fund additional hydrogen storage outside Delta, too, with more caverns carved into the salt dome.

One last wild card at Intermountain: that 732-mile electric line, whose route Rob and I were following when we stopped to tour the coal plant. The line is being planned by billionaire developer Phil Anschutz, along with a giant wind farm in southern Wyoming that will send renewable power to Los Angeles. The electric wires would pass right through the Intermountain site.

Anschutz’s power line and wind farm, assuming they get built, might end up having nothing to do with Intermountain, besides sharing airspace. Or they could supply some of the clean energy that’s needed to convert water molecules into hydrogen.

But that’s a story for another day.

Until then, here’s what’s happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

The number of California properties facing severe fire risk will grow from 100,000 to about 600,000 by 2050 as Earth heats up. That’s according to first-of-its-kind modeling, my colleague Alex Wigglesworth writes. The present is no picnic, either. A fire destroyed 20 homes along the Orange County coast last week on a humid day with no Santa Ana winds; it may have been sparked by Southern California Edison infrastructure, and the vegetation was so dry after years of drought that the mild weather hardly mattered, per The Times’ comprehensive coverage. Laguna Niguel residents who lost their homes were devastated, Hannah Fry reports. And it’s not just wealthy coastal homeowners at risk: Bloomberg’s Todd Woody reports that in the last two years, 73 Western summer camps were damaged or had to evacuate due to fire. You should also be careful when booking an Airbnb; my colleagues Ben Poston and Alex Wigglesworth investigated and found the company doesn’t require hosts to notify guests when they book in a high fire risk area, or how to evacuate. Here’s how to stay safe when booking an Airbnb, via The Times’ Karen Garcia.

The California Coastal Commission unanimously voted down a proposed seawater desalination plant in Huntington Beach, over the objections of Gov. Gavin Newsom and other supporters who said it would supply reliable drinking water as the region gets drier. Several commissioners said they see a role for desalination but were convinced this project would be too expensive and vulnerable to sea level rise, my colleague Ian James writes. With or without desal, drought solutions are badly needed — just ask the wealthy folks of Calabasas, who worry new water restrictions will affect their koi ponds and fancy cars, The Times’ Brittny Mejia reports. (OK, on second thought, maybe ask somebody else.) On the Colorado River, climate scientists and mob historians are sharing a rare moment of joint captivation and horror as water levels fall at Lake Mead, bringing dead bodies to the surface, Nathan Solis writes. A different kind of revelation is taking place upstream at Lake Powell, where the Salt Lake Tribune’s Zak Podmore writes that conservationists campaigning to drain the giant reservoir don’t seem so “looney” anymore.

Half a century after DDT was banned, it’s still accumulating in North America’s largest land bird, the majestic California condor — and that’s a sign humans are also exposed. So writes my colleague Rosanna Xia, in a story about new research identifying more than 40 DDT-related compounds circulating through marine ecosystems and accumulating in condors at the top of the food chain. It’s not great! In other coastal pollution news, the Associated Press reports that Plains All American Pipeline has agreed to pay $230 million to fisherfolk and coastal property owners as part of a settlement over the 2015 Refugio oil spill in Santa Barbara County. Further inland, volunteer divers pulled 25,000 pounds of trash from Lake Tahoe, The Times’ Parth M.N. reports.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas, Utah and West Virginia are suing to stop the Environmental Protection Agency from letting California set its own vehicle pollution rules. Details here from my colleague Nathan Solis. Elsewhere in Washington, D.C., House Democrats are alleging that Trump-era Interior Secretary David Bernhardt orchestrated a bribery scheme involving an Arizona housing development, which Bernhardt denies. Times columnist Michael Hiltzik wrote about the allegations, including a connection to Los Angeles Angels owner Arte Moreno. Speaking of Bernhardt, he was previously a lobbyist for Rosemont Copper, which just saw a federal court block its plan for an open-pit mine near Tucson, per Howard Fischer at Capitol Media Services.

Three years ago, the National Park Service estimated its maintenance backlog at $13 billion — and Congress passed a bill to pay down half of it. Now the park service has quietly updated its backlog estimate to nearly $22 billion, Kurt Repanshek writes for National Parks Traveler. It’s not super clear what’s going on, except that protecting treasured lands — and facilitating public access — is not cheap. And as the U.S. looks to protect more places — President Biden wants to safeguard 30% of America’s lands and waters by 2030 — there’s growing debate over the role of private lands, particularly farms and ranches. This story by Stateline’s Alex Brown does an excellent job exploring the debate. California, meanwhile, is acquiring 2,100 acres near the confluence of the San Joaquin and Tuolumne rivers to create the first new state park in 13 years, Paul Rogers reports for the Mercury News.

With Peninsular bighorn sheep populations recovering — including in Southern California’s San Jacinto and Santa Rosa mountains — state officials may downgrade the species from “endangered” to “threatened.” Here’s the story from the Desert Sun’s Erin Rode, who notes that the majestic beasts were first protected under the California Endangered Species Act in 1971. Elsewhere in the desert, a judge says the federal government wrongly denied Endangered Species Act protections to the bi-state sage grouse, a distinct sage grouse population along the California-Nevada border, as Scott Streater reports for E&E News.

AROUND THE WEST

In a good year, California farmers might plant 500,000 acres of rice — but this year it will be less than 250,000, hammering the Sacramento Valley’s economy. The Sacramento Bee’s Dale Kasler explores why the situation is so bad and how the dearth of flooded rice fields could harm migratory birds. In Southern California, the Imperial Irrigation District is hurrying to rein in farmers projected to use 92,000 acre-feet more Colorado River water than they’re allotted, the Calexico Chronicle’s Antoine Abou-Diwan writes. Are there lessons to be learned from a 200-year-old drought survivor? I’m not sure, but my colleague Gustavo Arellano communed with L.A.’s oldest palm tree to find out. He also hosted a drought-focused episode of our daily podcast, The Times.

After a series of plane crashes — and concerns over lead pollution — residents of L.A.’s Pacoima neighborhood are pushing to shut down an airport across the street from their homes. I had no idea that many small private planes still use leaded fuel; it’s one of several startling details in this story by The Times’ Rachael Uranga. Communities on the other side of the San Fernando Valley, meanwhile, are concerned about a different kind of pollution. It’s been 15 years since Boeing agreed to stringent cleanup standards for Santa Susana Field Lab in the Simi Hills, site of a partial nuclear meltdown in 1959. But that cleanup never happened, and critics say California is largely letting Boeing off the hook with a new agreement, Olga Grigoryants reports for the Los Angeles Daily News. See also my previous coverage of Santa Susana, and of the gas-fired power plant that also fouls the air in Pacoima.

New Mexico’s largest-ever wildfire has been burning for a month, and rural residents are growing increasingly frustrated with the government’s response. They’re not happy with “backburns” being used to to fight the fire right along their property lines, or with the possibility that a prescribed burn may be to blame for much of the conflagration’s spread, the Washington Post’s Karin Bruillard reports. At New Mexico’s Los Alamos National Laboratory, meanwhile, researchers are studying how to combat climate-fueled megafires as they prepare for the possibility of evacuation themselves, Morgan Lee writes for the Associated Press.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

Gov. Gavin Newsom wants lawmakers to approve a $5.2-billion “strategic electricity reliability reserve” to help keep the lights on the next few years, as heat waves worsen and California keeps phasing out fossil fuels. Details here from Dale Kasler at the Sacramento Bee, who notes that Newsom is also asking for $1.2 billion to help people pay their electric bills. That’s especially important considering that 3.6 million homes are in arrears after missing payment deadlines, as electricity rates rise faster than expected, per Rob Nikolewski at the San Diego Union-Tribune. Newsom’s revised budget proposal also includes expanded funding for lithium and geothermal energy development in the Imperial Valley, the Desert Sun’s Janet Wilson reports.

Sempra Energy has a new European client for liquefied natural gas, as Europe tries to reduce its dependence on Russian supplies. The San Diego company — which owns Southern California Gas and San Diego Gas & Electric — reached a deal to sell 3 million tons of LNG each year to Poland, from two export facilities on the Gulf Coast. Back in San Diego, SDG&E customers and climate advocates protested outside Sempra’s annual meeting as shareholders voted to approve raises for top executives despite rising electricity rates, Camille von Kaenel reports for inewsource. While Sempra plans to send more gas overseas, it looks like the Biden administration won’t hold any offshore oil and gas lease sales this year, the Washington Post’s Anna Phillips reports.

Flagstaff, Ariz., and Colorado’s Boulder County are beginning to invest in carbon capture to help meet ambitious climate goals. Details here from Grist’s Emily Pontecorvo, who writes that these local governments are some of the first to seriously explore removing carbon from the atmosphere (while also moving aggressively to cut emissions). On a related note, check out this haunting but beautiful short documentary, published by the L.A. Times, about environmentalists taking up residence in Northern California trees to try to block clear-cut logging. Large trees store large amounts of carbon, keeping it out of the atmosphere.

ONE MORE THING

“Last Week Tonight” host John Oliver hasn’t shied away from complicated energy issues on his HBO comedy program. This week was no exception, with the comedian ridiculing Pacific Gas & Electric (and other power companies) over what he sees as their propensity for igniting wildfires, bilking customers with exorbitant expenses and working to make rooftop solar less affordable. He also calls for performance-based regulation and gets electrocuted by a demonic version of utility industry mascot Reddy Kilowatt.

If Oliver doesn’t fill your weekly quota for utility criticism, see this piece by L.A. Times columnist Carolina A. Miranda calling out the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power and other water agencies for their lackluster graphic design in encouraging Southern Californians to save water. The DWP home page, for instance, “looks like it was last optimized for Netscape,” Carolina writes.

Personally, I’m a fan of the Imperial Irrigation District’s water and energy safety mascot, Dippy Duck.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.

For the record: Last week’s edition misstated the location where the Green and Colorado rivers meet. Their confluence is in Canyonlands National Parks.